The story of the 9mm vs .45 ACP is kind of a strange one. If you asked even self-described “gun people,” they would likely say that the 9mm is the newer cartridge, and the .45 ACP (or .45 Auto) is an old timer. The truth is that they were both created within just a few years of each other at the dawn of the 20th century, just as technological innovations and two impending world wars would change the course of firearms history.

These two cartridges were put up against one another in World War II, with the .45 going on to become America’s pistol cartridge (at least for a time) and the 9mm finding success overseas. Now the 9mm has been steadily winning the popularity battle, but the cartridge comparisons rage on.

While the U.S. military made the switch to the 9mm long ago, there is still a deep affection for the ol’ .45. Let’s dig deeper into how these two legendary pistol rounds stacked up when they were introduced, and how they compare today.

9mm vs .45 ACP Specs

9x19mm Parabellum

Ammo Encyclopedia

- Introduced: 1902

- Designer: Georg Luger

- Bullet Diameter: 9.01mm / 0.355 inches

- Case Length: 19.15mm / 0.754 inches

- Overall Length: 29.69mm / 1.169 inches

- Parent Case: 7.65x21mm Parabellum

- Max Pressure (SAAMI): 35,000 psi

- Bullet Mass: 7.45 grams (115 grain) – 8.04 grams (124 grain)

- Velocity: 1,180 fps – 1,345 fps

.45 ACP

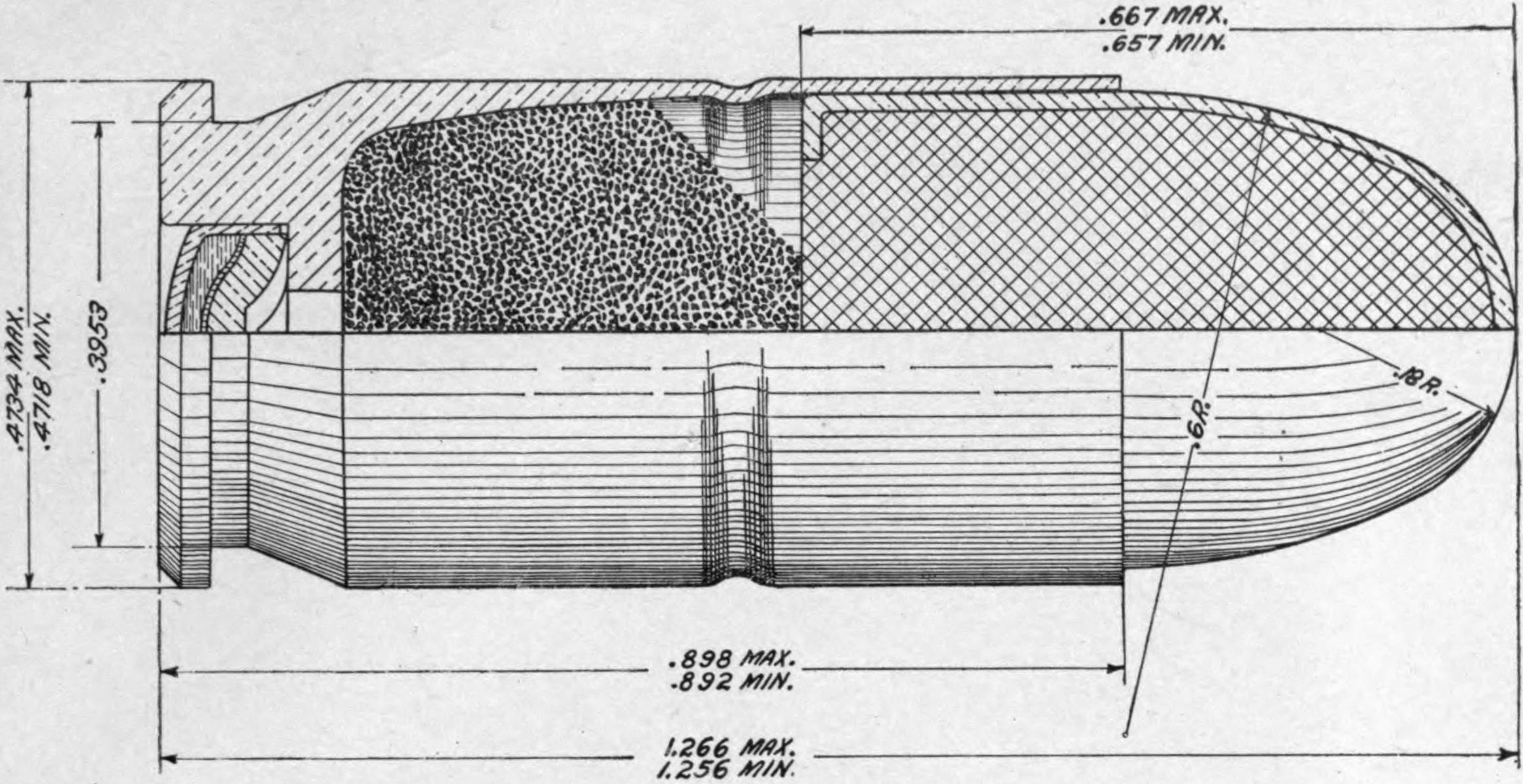

U.S. Army

- Introduced: 1905

- Designer: John M. Browning

- Bullet Diameter: 11.5mm / .452 inches

- Case Length: 22.8mm / .898 inches

- Overall Length: 32.4mm / 1.275 inches

- Parent Case: N/A

- Max Pressure (SAAMI): 21,000 psi

- Bullet Mass: 12 grams (185 grain) – 15 grams (230 grain)

- Velocity: 835 fps – 1,200 fps

History

9x19mm

Going by dates, the 9mm cartridge was actually developed first, so let’s start there. The rimless, tapered 9x19mm Parabellum was created by Austrian firearm designer Georg Luger in 1901 — four years before John Moses Browning dropped the .45 ACP. Like the .45, the 9mm was designed for a specific firearm: the Luger semi-auto pistol. That’s why it was originally given the moniker “9mm Luger,” which you still see in use today.

The original Luger pistol, patented in 1908, was a refined version of the Borchardt C-93 pistol, which used the 7.65x21mm Parabellum cartridge — the 9mm’s parent cartridge. The “parabellum” is derived from the latin motto used by the long defunct German arms company Deutsche Waffen-und Munitionsfabriken (DWM): “Si vis pacem, para bellum” (if you want peace, prepare for war.) You will still see this name used for the cartridge by people who pretend that they understand Latin.

Georg Luger created the 9x19mm cartridge in response to a request from the German military for a more powerful handgun cartridge. Remember that, because it’s going to sound real familiar real soon.

The Luger pistol chambered in 9mm came to be known as the German P08 pistol, and it would become a thing of legend. The gun and cartridge were presented to the British Small Arms Committee and three prototypes were sent to the U.S. Army for testing at the Springfield Arsenal in 1903.

Wikicommon

It was readily adopted by the German army and navy and the 9mm became the standard German pistol cartridge through World War II. As for the Luger P08 — it was produced until 1943 and issued through 1945 . It had a great reputation for accuracy and reliability (though the action could be a bit finicky in battlefield conditions), but it was slow and expensive to manufacture.

The P08 was replaced by the cheaper and simpler Walther P38, also chambered in 9mm, which was the first locked-breech DA/SA pistol. If you ever have the chance to handle one, you’ll notice a number of similarities to the later Beretta 92 series of 9mm handguns.

In 1935, a design begun by Browning was completed by gun designers at FN Herstal (Belgium), which produced the first Browning “High Power” pistols in 9mm. The name referred to the impressive capacity of the pistol’s double-stack magazine: 13 rounds. That was more than double the capacity of revolvers of the day and the 9mm Walther P38 and six more rounds than the M1911.

During the war when Belgium was occupied by Nazi Germany, the FN was used by the Wehrmacht to build the Hi-Power as the “9mm Pistole 640(b).” Meanwhile, FN Herstal continued to build the pistol for Allied forces on the other side of the Atlantic in Canada at the John Inglis and Company plant. That’s where it got its “Hi Power” moniker. This makes the Hi Power 9mm pistols one of the few firearms used by both the Allied and Axis forces during the war.

The 9mm went on to be adopted as the pistol cartridge and submachine gun cartridge of NATO and many independent nations. Today it’s the most popular handgun cartridge for many applications, including the military, law enforcement, and self-defense.

.45 ACP

The rimless, straight-walled .45 ACP, which stands for Automatic Colt Pistol, was designed by Browning in conjunction with the refinement of what would become the Colt 1911 pistol. It was the first cartridge adopted by the U.S. military for its first automatic/autoloading pistol, the M1911. The round was initially introduced in 1905, an age when semi-autos in the U.S. were considered finicky, underpowered little guns that jammed all the time — because, well, they mostly were.

But what set the stage for this big change in military handguns before WWI?

As the 1800s became the 1900s, the U.S. military began to modernize in spurts. First the U.S. Calvary wanted to replace its .45 Colt Peacemakers with double-action guns. Then the Army started to adopt double-action wheelguns chambered in .38 Long Colt. But those guns infamously underperformed against the Moro warriors in the Philippines during the Moro Rebellion with reports of the light cartridge failing to bring down combatants after multiple hits. Army ordnance member Gen. John T. Thompson called vehemently for a more powerful cartridge, and he was heard. But in the meantime, they dug the old .45 Colt guns and ammo out of mothballs.

Browning had been working with Colt to develop a .41 caliber cartridge. In 1905, after tests and studies, the military came calling for a round equivalent to the .45 Colt for a semi-auto pistol. Browning sized up his prototype .41-caliber round and the pistol he was working on. The result was the Colt Model 1905 and the .45 ACP cartridge.

Wikicommons

That original .45 was topped with a 200-grain bullet and had a velocity of about 900 fps. After further testing with the dominant ammo-makers of the day, the “standard” .45 ACP we know today became a 230-grain bullet with a velocity of 850 fps.

It hit like a .45 Schofield and was a lot shorter and lighter than the .45 Colt with less recoil.

But the Model 1905 wasn’t the right gun. It needed refinement, and other pairings with the .45 ACP had to be considered. In 1906, the military took a look at submissions from six gun companies. The guns from DWM, Savage, and Colt moved on. DWM put up two Lugers chambered in .45 ACP (highly prized handguns today), but withdrew them from testing early on.

The second round of trials was held in 1910 (yeah, government moved super slow even then) and the Colt outperformed the Savage pistol with zero stoppages versus 37 stoppages or parts failures.

So, the Colt pistol was adopted as the M1911 and the Savage pistol hit the consumer market as the Savage 1907 pistol, though the only models to ever be chambered in .45 were the trial guns. It went to market in .32 ACP and .380 ACP.

The single-action M1911 became the M1911A1 during WWII. The pistol and its cartridge remained in service until 1985 when it was replaced by the DA/SA Beretta M9 (developed from the Beretta 92FS) — chambered in 9x19mm. It remained in service until 2017 when the Army was the first branch to announce it was switching to the M17 and compact M18 pistols, derived from the striker-fired SIG Sauer P320 handgun platform.

Performance

9mm

Handgun shooters have adopted the 9mm in droves for two reasons, flat trajectory and moderate recoil. Some people describe the recoil of very compact 9mm pistols as snappy, usually meaning there is a lot of muzzle flip, which can be an issue for really small guns and small shooters. But in a full-size pistol, the recoil of a 9mm is extremely manageable for the majority of shooters.

There was a time when the 9mm was called underpowered by some — usually folks who carried .45s. Then came the introduction of the .40 S&W and critics said it would be the end of the 9mm. Law enforcement agencies all over the country adopted the new cartridge, which was sold on being more powerful than a 9mm, which “could bounce off a windshield” while not taking up as much magazine space as a .45.

In reality, .40 S&W pistols did have a decreased mag capacity compared to their 9mm counterparts and the round generated higher pressures than a 9mm, meaning it had more recoil and it was rough on guns. Plus, 9mm ammo technology advanced so quickly, soon the .40 S&W’s ballistic advantages were overshadowed by +P 9mm loads topped with modern bullets.

After flip-flopping around from the 9mm to the 10mm to the .40 S&W and then back to the 9mm, the FBI released a report in 2014 saying that when comparing 9mm, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP cartridges developed for the agency, the new propellants and bullet design used by modern 9mm defensive loads were comparable to the other two larger rounds while also delivering less recoil, greater mag capacity, and less wear on firearms.

After a brief dalliance with the .40 S&W, many U.S. law enforcement agencies now use 9mm handguns — as many as 60 percent, according to according to Newsweek.

Read Next: Best 9mm Ammo

.45 ACP

Photo by Tanner Denton

The .45 ACP is one of the few larger cartridges that’s actually easy to shoot in full and medium sized handguns. It has relatively little felt recoil and muzzle flip — it thuds rather than snaps and is easy to control for many shooters, even newbies. This changes when you get into subcompact handguns, where the .45 can be a bit of a mule.

You will often hear that a .45 has more “stopping power” than a 9mm. Instead of getting pulled into silly stopping power or knockdown power debates, what you should know is that a .45 bullet is large and wide with a fair amount of mass that’s moving relatively slow. It creates larger wound channels sending most of its energy into a target, as opposed to a smaller FMJ bullet that will often punch a hole through a target.

That dichotomy was true for a long time during the non-expanding full metal jacket days, and it helped build the .45’s mystique. The bullets would often penetrate deeply without passing through the target. Fans of the .45 argued that with that kind of power, it was of little concern that a 1911 only held one or two more rounds than a revolver in .38 Special.

The .45 continued to be a powerhouse with modern expanding bullets, but it has drawbacks. As we know, the cartridge is short, but it’s fat and heavy. Even in double stack magazines you’re looking at a capacity of 12 rounds, or 14 at most with an extended mag.

Extended mag 9mm pistols can hold 20 rounds today, and even the oldest Hi-Power mags held 13 rounds. Single stack .45 mags are still 8 rounds max.

Also, the .45 ACP, due to its low velocity, starts dropping fast and isn’t very reliable at distance, even from carbine-length barrels. Comparatively, the 9mm can be pushed out to greater ranges. This doesn’t matter much for most self-defense scenarios, but it makes the 9mm more versatile, especially in submachine guns and 9mm carbines.

However, that fat, slow round works well with suppressors: at standard pressures, most .45 ammo is already subsonic, which is great for sound reduction at the muzzle. That said, they are still pretty loud compared to a suppressed 9mm running subsonic ammo.

Read Next: Best 1911s

Takeaway

In the end, the 9mm vs .45 ACP debate comes down to versatility. Modern .45 ACP ammo and .45 handguns are excellent for close encounters of the human variety where you aren’t likely to need more than 8 to 12 rounds. That covers the bases for a lot of people when it comes to self-defense, and in states with magazine capacity restrictions, choosing a .45 doesn’t mean sacrificing ammo capacity.

Some people just shoot a .45 better, and in the end, shot placement is still the most important factor.

But compared to the .45, the 9mm cartridge is wildly versatile with a bevy of ammo options available for all appropriate applications. Magazine capacities are high, the magazines themselves are plentiful, and so is ammunition (typically). There are also tons of options when it comes to projectiles, and modern +P loads are no joke.

Modern 9mm handguns also do a lot through their design, such as the low bore axis on many popular striker guns, to mitigate muzzle flip. Other models lean on ports or some kind of compensator for that task, like Smith & Wesson’s expanding M&P Carry Comp line, while others are adding a little weight to 9mm pistols for those who want it by using steel frames instead of full polymer. There’s a wide variety of Micro 9mm pistols, which are much more comfortable to carry for many folks.

Plus, the flat trajectory means the 9mm is easier for new shooters to master at a variety of distances. And the 9mm performs well in Pistol Caliber Carbines. Today, the 9mm is king, but that doesn’t mean the .45 is obsolete by any means. It still does everything it always did well, and it’s still a popular choice for many shooters for all handgun applications. The old warhorse from John Browning’s workshop will likely be around for a long time. So, why get into this argument at all? Just make sure you own a 9mm and a .45, and keep the peace between the calibers.