This story by our former longtime shooting editor originally ran in the October 1997 issue.

THE TWO QUESTIONS I’m most often asked are: “How did you become a gun writer?” and “What is your favorite gun?”

There seems to be a widespread notion that gun writers are anointed by Diana, Goddess of the Hunt, and dwell thereafter in a magic kingdom filled with luscious firearms, like a fat Sultan surrounded by a harem of delicious maidens. The fact of the matter is that if I gave honest answers to either of these two questions I’d be accused of inventing stories or pulling my questioner’s leg. That’s why I usually render a modest response that suits the occasion or simply leave the subject hanging in the air, especially when it comes to the matter of favorite guns. Who would believe me if I tried to explain that I have torrid-but-fickle love affairs with shotguns, and that last season’s undying passion now reposes on the dark side of my gun rack?

In any event, like wives and mistresses, “favorite” guns are usually a matter of personal taste. The guy down the street may think the .30/30 he inherited from Dear Old Granddaddy is the sweetest thing in the deer woods, while you wonder why he bothers to take the clunker hunting. So with advance warning of these caveats, and since someone asked, I have a few favorites worth mentioning. My current favorite shotgun, like all properly conducted love affairs, shall remain secret. Rifles, on the other hand, tend to be more honest and businesslike and, unlike svelte smoothbores that blind you with coy promises, can be ranked according to how well they do their job, and why. But even then, as we shall see, reason sometimes gives way to sentiment.

FROM THE STANDPOINT of unrivaled hunting perfection, my favorite has to be a .338 Winchester Magnum built by the David Miller Company. If you’re an aficionado of hand-built rifles you know that the “economy” model Miller rifle now sells for something in the neighborhood of eight grand, with deluxe grades having gone for over $200,000 on the auction block…which probably makes you wonder how an impoverished gun writer comes by such pricey hardware. The simple explanation is that I got my Miller rifle about 20 years ago, before wealthy sheikhs and oil tycoons discovered the remarkable talents of David Miller and Curt Crum, his stock-building partner.

Miller had developed a scope-mounting system that he was proud of and asked me to give it a try. During our conversation, I learned about his budding rifle company and the upshot was that I had him build a rifle in .338 Mag., complete with the new Miller mount. The funny thing, however, was that I somehow got the idea that Miller’s mounts were a quick-detachable system, so I figured that a set of English-style express sights would round out the rifle to perfection. I was doing a lot of jetting back and forth between Alaska and Africa in those days, and a .338 Win. Mag. would be good medicine for just about anything that roamed the veld or tundra, especially if fitted with some fast-pointing express sights for those tedious and aggravating moments when lions come roaring out of the yellow grass.

So that’s why the Miller rifle came complete with stylish express sights fitted. The quarter rib on which the rear sight is dovetailed is not simply soldered to the barrel in the usual way, but actually machined from the barrel blank so that they are one integral unit. But alas, as it turns out, this tour de force of metalworking is of no practical purpose, because I have yet to squint across the elegant express sights, the reason being that the Miller system gives whole new meaning to the phrase “permanent mounting.”

The base and lower half of the rings are machined from a single block of steel and form a rigid cradle that supports and protects the scope for almost the entire length of the tube. Before building his scope mount, Miller needs exact information about the customer’s shooting stance and eye positioning, because once the base is machined to interlock with the scope turret, any fore or aft movement is impossible. And to further reduce the likelihood of scope movement, the rifle’s receiver ring is notched to form a recoil lug-type union with the scope base. The one-piece scope cradle is then mated to the action so precisely that they appear to be a single unit.

When Miller introduced this super-strong, scope-mounting system the price was $300—a staggering sum back then considering that ordinary mounts could be had for about $10 bucks. But big-ticket hunters who’d lost trophies because of inferior mounts considered the Miller system a bargain. In time, the price for a Miller mount climbed to $900, and if that makes you gulp, consider that it now sells for $1,500! But the only way you can get one is by ordering an entire David Miller rifle.

Is it worth it? All I can say is that for nearly two decades of hard hunting in temperatures ranging from 20 below zero to 110 above, in rainstorms and desert dryness, the only time I’ve touched the adjustment knobs on the rig’s 4X Leupold scope was the first time I sighted it in. Since then it has been spot on.

DON’T GET THE IDEA that my David Miller .338 is a favorite only because of the foolproof scope mounts. Actually, the Miller mounts are just one element of a total hunting machine. Nothing has been left to chance, from the rebuilt Mauser action, to the Model 70-style safety, to the raised checkering on the bolt knob, to the hinged floorplate on the magazine that has been “dropped” English-style so that capacity is increased by an extra round, to the gracefully curved trigger so closely fitted in the guard slot that seeds and grit can’t work their way into the mechanism. Then everything is perfectly fitted into a luscious piece of smoky-hued French walnut, with classic styling by Curt Crum and checkered with a delicate fleur-de-lis pattern.

The years and the miles have left their scars on my David Miller rifle the blue is getting thin on some of the corners, and every hunting season I find more scratches on the stock. Miller has invited me to send the rig back for a touch-up, but I don’t think so. There is honor in those dents and nicks—each with its own story to tell. When I grow too old to climb the hill and chase the plain, I want to touch those scars and hear the stories again.

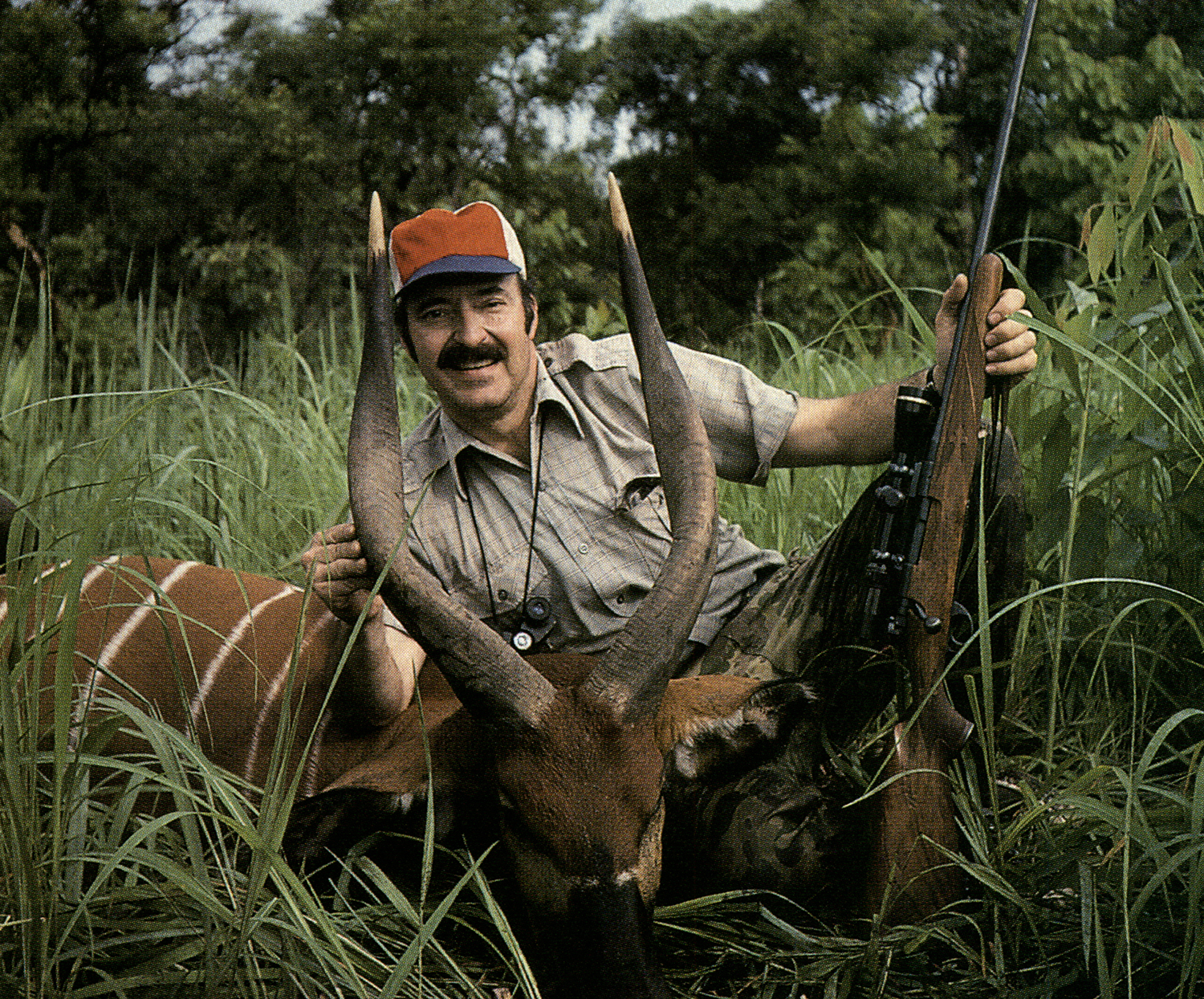

Another favorite that has graced my rack for more than two decades is a custom flyweight built on a pre-1964 Model 70 Winchester action and chambered in .280 Remington. The slender barrel is by Douglas, and the exquisite Clayton Nelson stock is that amber-streaked kind of French walnut that we can no longer find. I’ve long since lost count of the deer, elk, sheep and African-plains game this lovely .280 has taken, but, for the record, it is the rifle I took to Iran back in the 1970s when my pal Fred Huntington and I went there to collect the Iranian “Grand Slam” of ibex, red and urial sheep and the petite Armenian sheep.

One sad day, when I was hunting elk in Idaho, I left my horse tied to a tree while I glassed a canyon. Another horse, tied nearby, spied the unprotected French walnut butt of my rifle jutting from the scabbard and, being an ugly and unprincipled beast, figured it would be a handy thing on which to rub his chin. That chin, of course, was wearing a steel bridle bit that cut long gashes in my lovely rifle.

My tears were a long time drying, and after that tragic event the rifle was hunted with only once more—when I took it to Alaska for white sheep. Guns, like good hunting dogs, deserve a graceful retirement, and after having the stock repaired and refinished to its former radiance, I retired the faithful rifle to a place of honor in my rack.

Its replacement, a .280 Remington built by Ultra Light Arms, rates about a 2 out of 10 on the beauty scale but earns its keep-and a place in my heart-because it can cut three overlapping holes in a 100-yard target and (even better) because it weighs less than six pounds, scope and all. This little Ultra Light isn’t really a favorite yet, but it will be, wait and see.

For sheer handling joy, I like a 7×57 built on a Mauser action by Al Bieson, a living legend in the custom-gun world because of his exquisite styling and craftsmanship. Though the Bieson rifle is gorgeous to look at, its real beauty comes to life when you snap it to your shoulder. I like to hand it to guys who think they know all about guns and watch their eyes light up when they experience for the first time the feel of a truly great hunting rifle. When you close your hand around the gracefully slender grip the rifle seems to find the target with a will of its own. This is a difficult quality to describe. British gunmakers often call it “hand”-the way a gun becomes a living part of the shooter-but usually in reference only to shotguns. A rifle with hand is a rare treasure, and everyone who takes this jewel in hand instantly understands why.

IF YOU’LL EXCUSE a moment of sentiment, one more favorite is a mildly battered and not particularly handsome .458 Winchester Magnum that was custom-made from a $30 surplus Mauser. Actually, a real maker of custom rifles would call it an amateur’s do-it-yourself project, and I suppose that’s all it is. I’m the amateur and it really was a do-it-yourself project from my college days. I’d found the slick Mauser in a junk store and, since I fancied myself something of a gunsmith back then, elected to convert it into something useful in the way of a big-game rifle. I mean really big game: elephants for example. My school chums hooted at the idea because they figured the chances of my going to Africa and bagging an elephant were about the same as Marilyn Monroe calling me for a date. Not that I was all that convinced myself, but the more they chuckled the more determined I became to at least own an elephant rifle.

To that end, I opened up the Mauser bolt face for the larger Magnum rim, had a .458 barrel fitted and laid out some $60 (big money in those days) for a classic-styled, semi-finished stock. After a couple of months of whittling and sanding and hand-rubbing stock oil, I had what I thought to be a rather elegant custom .458 and I promised myself that someday, somehow, I’d take that rifle to Africa and bag elephants, Cape buffalo, lions and other deadly beasts. It was a promise kept a decade later in a mopane thicket along the southern edge of Botswana’s mysterious Okavango Swamp, when I put the crosshairs just below the ear on an old bull elephant carrying thick, heavy ivory. On that and other safaris the do-it-yourself “elephant rifle” my school chums had laughed at tallied not just elephants and lions, but scores of Cape buffalo. Now it is hunted with no longer and rests in a special rack on the wall of my den, serving as a daily reminder that dreams will come true if you dream hard enough. It was the first rifle in my big-game battery…and the last I’ll ever part with.

Read more OL+ stories.