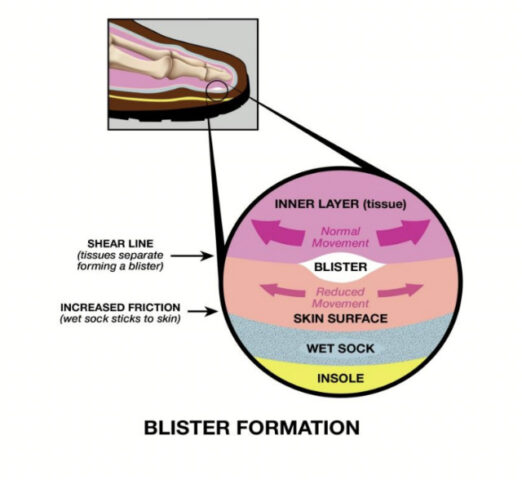

Hot spots and hiking blisters occur when increased friction from your footwear causes the outer layers of your skin to separate from the inner layers, a process called “shear.” When the layers of skin separate, the resulting void is filled with fluid creating a blister. This fluid leaks in from neighboring tissue and is “designed” to cushion the wound and accelerate healing. Left alone, the fluid will reabsorb into your skin when the layers of skin bond together and the blister heals.

How to Treat Hot Spots

A hot spot is a precursor to a blister and it’s best to stop and treat it immediately before it gets worse and turns into a blister. Really, don’t put it off or you’ll be sorry. When you feel a hot spot forming, it’s important to reduce the friction causing it. One way is to tape it with a piece of “shiny” tape with a smooth exterior like duct tape. If the hot spot is very painful already, cover it with a Band-Aid or a small piece of gauze to cushion it before covering it up with duct tape. This will make it less painful when you pull the duct tape off.

But duct tape isn’t a great remedy if the hot spot is on your toes because the tape itself can rub against your other toes and create another hot spot or blister. Vaseline is often a better solution because it reduces friction and also helps to soothe irritated skin. Alternatively, a small toe-sized band-aid with a slippery exterior may also provide friction relief. Changing into a dry sock can also help if your previous one is wet or sweaty because perspiration can exacerbate friction, especially if your shoes are tight.

How to Pop Hiking Blisters

1. If you have a blister that hasn’t popped yet and isn’t too painful to walk on, it’s best to keep it intact to prevent an infection. The fluid in the blister will be reabsorbed into your skin as it heals. Smothering it with a lubricant like Vaseline, and covering it with a small toe-sized band-aid or duct tape will often reduce the friction that caused it, so you can continue hiking.

2. If the blister hasn’t broken but is too painful to keep hiking, popping it and draining the fluid or blood inside is usually your best bet. Clean the skin on top and around the sides of the blister with a sterile alcohol wipe. Sterilize a needle or the tip of a pocket knife with an alcohol wipe or a butane lighter and poke a small hole in the side of the blister, releasing some of the fluid or blood within.

Keep the skin over the blister intact to keep it moist and prevent infection. Next, massage the remaining fluid or blood inside the blister out of the hole. At this point, I like to cover the blister with a cushioned Hydro-seal Band-aid. These band-aids (available in toe, medium, and heel sizes) absorb the remaining fluid and plump up like the body’s natural cushioning to protect the wound while helping to accelerate healing. They stay on securely if you get them wet and then fall off naturally after a few days to a week when the blister has healed. These Hydro-seal band-aids are the best solution I’ve ever found for hiking blister care and I carry a bunch in my first-aid kit. They’re the same as a product called Compeed in the UK.

3. If the blister has already broken or torn open, I still try to keep the remaining skin on it. But first, I sterilize the area around it with an alcohol wipe and then wipe the inner skin as well…which will hurt like hell. Next, I cover it with a Hydro-seal Band-aid as previously described.

4. If you get a blister that’s giant and simply too painful to walk on covered or not, take a few days off or however long it takes and let it heal. Don’t be stupid. Take it as a lesson not to let things get out of hand by ignoring a hot spot in the future.

See Also:

SectionHiker is reader-supported. We only make money if you purchase a product through our affiliate links. Help us continue to test and write unsponsored and independent gear reviews, beginner FAQs, and free hiking guides.