THE ERUPTION was so swift and violent that for a second I thought it had ripped open the bateau’s seams. I pushed hard against the gunwale to steady us, then threw up my hands to protect my face. A deluge of water sloshed me from hat brim to belt. When it subsided I looked up and saw Ted still on his feet staggering in the bow. The muscles of his forearms suddenly knotted and his rod snapped straight, knocking him for a loop and almost spilling him overboard. He fell into the seat.

“Let’s get out of here before one of those briny tigers drowns us,” I gasped. Ted Henson cackled like he’d laid an egg.

“Not on your life,” he shouted. “If these fan-tailed monkeys think they can keelhaul me they’ve got another think coming.” He started to rig up again, and I jabbed my paddle in the inky water.

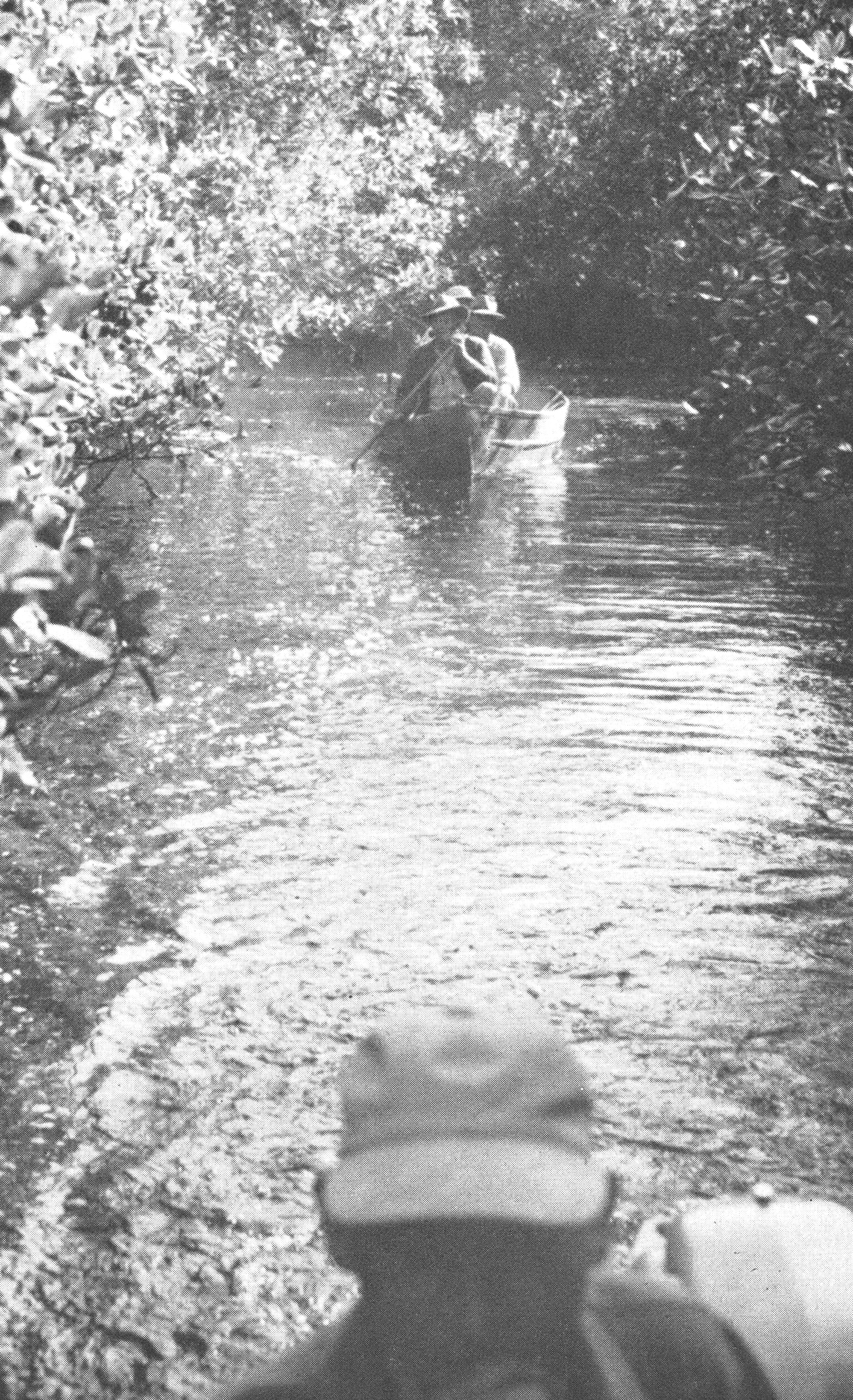

The twisting water trail, winding down its glaucous tunnel, looked as peaceful as the inside of a church. But I knew better. Below its placid surface were some of the most vicious creatures I’ve encountered in over 40 years. All my fishing life I’d searched for such a place as this, but now that I’d found it I was ready to swap it for a spot not quite so overpowering.

What amazed me more than anything else about this wild region was the fact that it has stayed undiscovered for so long by the angling clan. Stretching for about 50 miles in the northwestern section of Florida’s Everglades, it lies between the well-traveled Tamiami Trail and the heavily fished Ten Thousand Islands from Marco to Lostman’s River.

A MILLION ACRES or more, it is a vast open pasture of head-high saw grass networked with mangrove islands, oddly shaped lakes, and countless creeks and rivers. Its waters are lined with snarled mangrove roots and canopied with dense foliage. It is as isolated and virgin as the vast tundras on the top shelves of the continent. Protected on one side by treacherous bogs, and on the other by distance and shallow bars capable of trapping a boat at almost any stage of tide, it is a natural spawning ground for unnumbered species of salt-water fish.

Ted was on his knees in the bow, rattling around in his lures and looking for one of the same color as that which had been so rudely smashed off the end of his line. He’d left his tackle box on the dock and had piled 100 lures in a cardboard container which he’d been keeping close by him in the boat. Long ago I’d lost count of the plugs he’d lost, and was wondering if his assortment would hold out until noon. The mistake I made was in wondering out loud. Ted cocked a sweaty, sun-scorched face at me and then reached over and jabbed the rod butt into my hand.

“Since you’re so smart,” he rattled, “let’s see you handle them.”

Ted held the line and tied onto it a plug the color of country butter and sparsely speckled with yellow, brown, and crimson dots. I’d have picked it as the lure least likely to succeed, but every one of its mates we’d dunked that morning had driven the fish insane.

“Throw it,” Ted dared, “throw it and hold on to your hat.”

The jungle pressed down too close for an overhand cast, but the trail was just wide enough to give the six-foot rod a horizontal motion. I flipped the chunk of bright wood into a dark nook.

Since daylight I’d watched Ted retrieve in short, swift jerks that gave the lure a darting action, like a minnow fleeing for its life. I’d given that line exactly three jerks when a vicious strike almost snapped my wrists. It was a tremendous snook, a robalo, or as the Florida swampers call it, a snuke.

I BRACED both knees against the rim of the bateau and hung on. The monster threw himself into the air with the power of a tarpon and the speed of a rainbow trout. He hurdled a crooked mangrove stem, beat the water into suds, flung himself clear again, and then plowed headfirst into a tangle of roots. That was all. There was no stopping him, no turning, no checking. His lightning run broke the line and left me rocking. As I fell against the seat Ted giggled like a crazy mermaid.

I pawed through the cardboard box for another of those candy-colored plugs, but the one I’d just been relieved of was the last. So I picked one of a color that almost matched and clinchknotted it directly onto my heavy leader. We’d started fishing with snap swivels, but a hard-hitting snook had put an end to that by straightening the tiny wire of my swivel on its first ferocious strike.

I hooked a three-pound fish on my off-color lure and turned it back. I raked the crannies with a dozen casts that failed to produce, so I changed to a lure Ted selected. This bit of hookhung wood proved even less attractive to the fish, so I tied on a bright silver floater and laid it beside an old log. A jack crevallé took it on the run. He wouldn’t go two pounds, soaked to the gills, but he gave my weapon a workout before I shook him off.

I changed places with Ted, and on the third cast he picked up a baby snook not much bigger than the plug. Ted threw him back and put his rod in the boat.

“What would you say,” he asked, turning to me, “was the first rule of snook fishing?”

“Carry a tackle manufacturer with you at all times,” I replied.

TED NODDED and cranked the motor. Ike Walker, whose business and pleasure in life is the manufacture of fishing lures, was somewhere south of us on the creek fishing with Grady Blanton and Milton Pace. Ike had made the trek into this brackish wilderness for the sole purpose of finding out what kind of lures the big snook find irresistible. He’d brought along hundreds of plugs of every imaginable color, size, and action, and from these we’d selected half a dozen patterns which we’d found most productive. The one we nicknamed Candy was head and dorsal the prize whammy on snook.

I relaxed while Ted guided the boat along the tortuous run. A movement in the arched branches caught my eye, and a huge raccoon scampered along the aerial pathway from one side of the creek to the other. He was only one of many we’d seen that morning. The mangrove roots within arm’s reach of us were alive with sand crabs-tidbits to coons-and I was amusing myself watching them when Ted suddenly swung the bateau at a sharp angle. “Look out,” he yelled.

I didn’t know whether to dodge or jump, and had no time to do either before I got a glimpse of an alligator as long as our boat. We’d startled him out of his morning nap, and Ted had swung the bateau just as the monster lunged for the protection of deep water. Somehow he managed to get under us, but his leathery tail hit the boat a terrific smack and sent enough water skyward to make a good-size squall.

As we putted along, the only signs I saw of other anglers was an occasional beer can hung on a bush. Ted noticed me looking at one.

“That,” he said, “was put there by Little Tiger.”

I’d heard about Little Tiger. He was a Seminole guide who lived across from the main road and had been Ted’s escort on a couple of previous trips into this never-never land. We’d spent most of one night trailing him until the road ran out and left our jalopy stuck to the hubs in muck and sand. We’d planned to offer him plenty of greenbacks to take us to a lake where he’d refused to carry Ted because he said it was bad luck.

I’ve seen some classic roping and bulldogging in my day, as well as some unforgettable conflicts with fish, but I’ve never witnessed anything like the fight Grady had with that snook.

The two of them had twice started out for the hidden lake. The first time they met a tremendous manatee in a deep run. It was almost as large, Little Tiger said, as one he’d roped in the canal that runs by his village. He tied his line to a bridge and the big sea cow pulled both bridge and Little Tiger into the drink.

The second time, Ted was reaching for a low limb to help keep the boat straight when Little Tiger hit him between the shoulders with his push pole and knocked him out of the bateau. A water moccasin the size of a baby python was stretched across the limb. On both occasions Little Tiger refused to go farther because he declared he’d been given infallible signs of oncoming disaster.

Ted was saying he didn’t think we’d run into Little Tiger on this trip when we rounded a bend and swept into an open river. The sunlight almost blistered my eyeballs before I caught a glimpse of Ike Walker’s boat ahead. As we glided up to them, Blanton held up a good snook he’d just brought into the boat.

“If you’re looking for more of those Candy plugs,” Ike said, “you can keep going.”

“You’ve got them hid,” Ted accused. “Dig ’em out.”

“We’ve lost all but two,” Ike insisted. “I’ve got to save those for models.”

“Save one,” Ted suggested, “and we’ll save the other.”

Ike grumbled, fumbled in the bushel of plugs scattered around his boat, and came up with a Candy that was scarred with teeth marks.

“It’s the last one,” he begged. “Don’t fish it under those mangroves.”

We refilled Ted’s paper container with a hatful of other artificials and turned toward the dock to pick up Grady Cushing. Grady had assured us that he knew where Little Tiger’s unlucky lake was. He hadn’t fished it for more than a year, he said, but on his last trip took snook out of it as large as those that had smashed our tackle in the runs. He was waiting for us, armed with a casting rod that was so short it made ours look like television antennas. Ted reached for the sawed-off tubular glass.

“How long?” he asked.

“Three feet,” Grady said, “and it’s loaded with 40-pound-test line. Want to try it?”

Ted laughed. “No, thanks. I don’t crave hand-to-hand combat with those bruisers.”

We turned and went back up the jungle trail, and as we did so Grady studied the water that was rising in the run.

“Believe the tide’s high enough now. We can take a short cut to the lake and save an hour’s run.”

We turned off the deep trail and plowed into a sheet of open water that wasn’t spread much thicker over the marsh than a windowpane. Ted cut his motor to slow and we flushed a flock of bluewing teal feeding in a shallow neck.

“Those birds should be in the Arctic Circle making love,” I said. Grady wagged his head. “They nest here.”

LIFE IS ABUNDANT on this vast watery prairie. We flushed flocks of colored birds, white ibis, and hawks. Almost every 100 yards we surprised big snook that took off and left wakes like runaway torpedoes. I wanted to stop and throw the Candy at them, but Grady said no. He allowed that a chunk of wood that size would run those snook clean ashore.

We squeezed through a narrow pass in the saw grass which only Grady and Little Tiger could have known about. The tide was almost high. It shoved us right up under the overhanging limbs, and often we had to lie down in the bateau to get through. We churned through a succession of lakes, each a little deeper than the last, and just before noon came out into a wide body of water the color of chocolate and that seemed to be about eight feet deep.

Grady turned his head without moving his shoulders, like an Okeechobee owl. “Put your tackle under the seat,” he warned, “and don’t fall overboard. The snook in here are big as crocodiles and just as mean.”

“Does this lake have a name?” The Floridian flicked his eyes at me, good-naturedly. “We call it the Calamity Hole.”

It was alive with fish. Mullet were jumping everywhere I looked, and heavy boils around the boat strongly suggested that the snook were large and hungry. Ted and I both reached for the Candy plug, but Grady shook his head.

“Better go ashore and have our lunch first,” he said. “You’ll need the strength.”

MY INSIDES were slamming around with the beauty of the place and the excitement of being in a spot few white men had seen. Grady pushed the boat to an open, grassy bank and jumped out, and I dutifully passed him the sandwiches and coffee jug.

I wolfed down my sandwiches, poured a slug of coffee on top of them, and stalked up and down the bank wondering if my partners thought they were holding a wake.

“Stop loafing,” Grady called, “and toss a lure to that fish boiling off the point.”

“But don’t use that Candy plug,” Ted yelped.

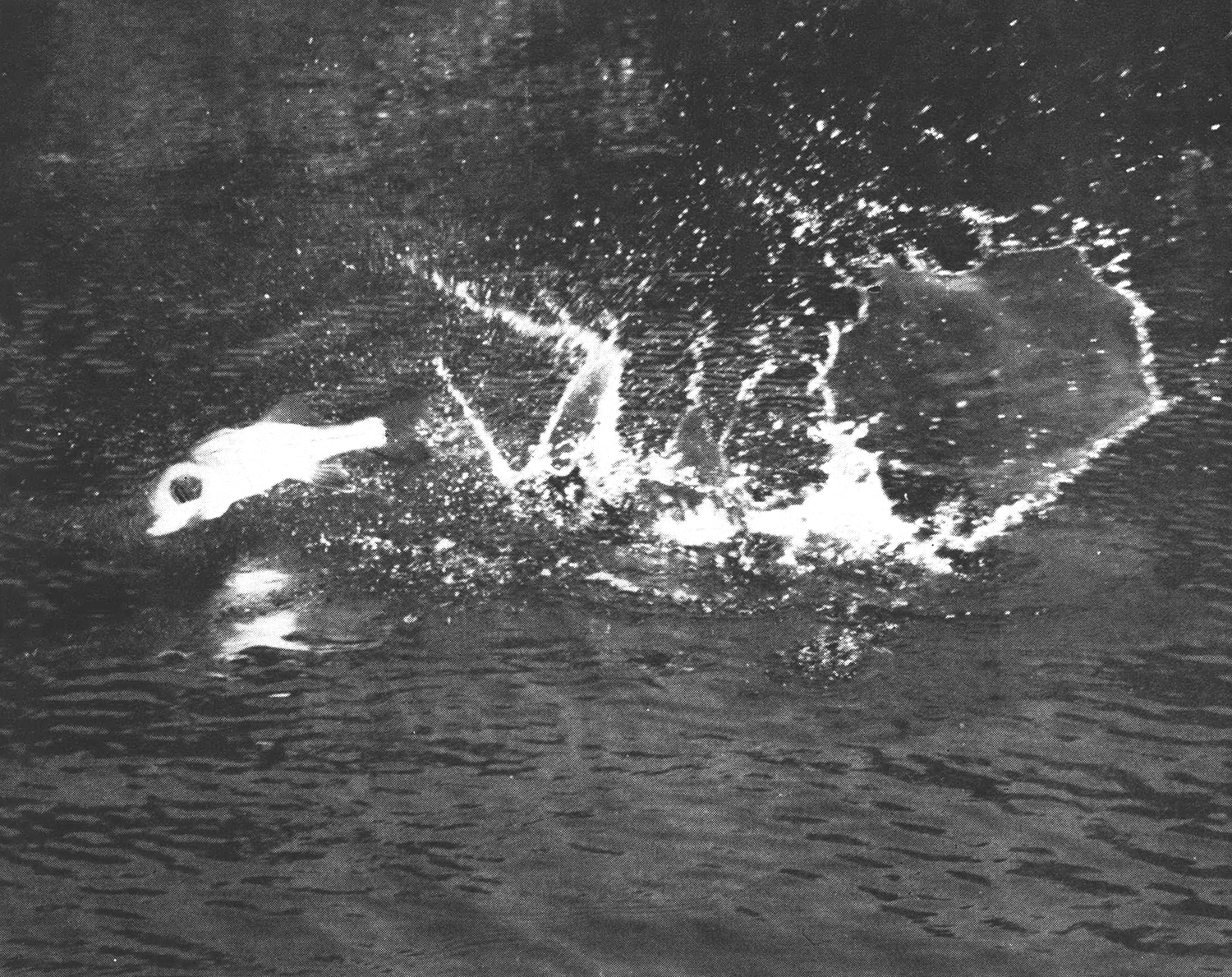

I dug a yellow, polka-dotted lure out of the pile, tied it on, and tested the gut and line. The fish swirled again, and I threw the saffron bait two feet beyond him. He met it at the surface. When I jabbed the hooks home he shot a good five feet into the air and stretched the nylon like a telephone wire. At the top of his thrust I turned him over and threw him hard against the surface. He bounced and took off like a marlin, whiplashing for 50 feet on his tail.

He jumped again and I crushed the palm of my hand against the reel to stop it, but I wasn’t fast enough. The whirling spool snarled the line into a knotty tangle and the sprinting snook snapped it like a strand of blond hair.

I licked my skinned knuckles and looked around. Ted was choking on a sandwich and Grady was watching me with an amused glint in his eye. I put the rod back in the boat.

“There are plenty of plugs,” Grady said with a smile.

“I’d better save my fingers,” I replied, “I may need them again sometime.”

We packed our empty food containers in the boat and, with Ted in the bow and me between them with my camera, Grady poled us slowly into the middle of the lake. There Ted had 100 yards or more of battleground all around him.

The next hour was one of the brightest highlights of my fishing experience. Those snook took everything Ted offered. They hit anything that darted, moved, wiggled, or quivered. I decided that if my hat fell overboard I wouldn’t dip a finger in the water to pick it up.

I quickly ran out of film, and with nervous fingers locked the camera back in its case. Ted heard the snap click and, without glancing around, handed me my rod. I got the lure into the middle of the lake and gurgled it toward the boat. A husky snook slashed at it and missed. “Speed it up,” Ted yelled.

The fish took enough line on his second lunge to make the reel whine, and then went into the air. I got him in finally, and Grady hefted him on the gaff. “Fifteen-pounder, at least,” he said.

Ted was fighting one with his spinning tackle. The monofilament was making like a bandsaw. I lost count of the fish we hooked and landed. After each cast we argued with Grady to give up his push pole and take one of the rods. But Grady wouldn’t.

“Get your bellies full,” he said. “There’s one spot I’ll try between here and home.”

The ligaments in my arm finally gave out, and my wrist and forearm got so sore I couldn’t keep a tight line. I began to lose fish or plug on every cast. Grady squinted at the sun.

“Maybe we’d better get going,” he said. “The short cut’s dry and it’s a long way home.”

I noticed for the first time that a dozen runs led out of the lake, and each was exactly like the other. The first shadows of late afternoon had brought out the mosquitoes-vicious, hot-needled gangsters that would die for a drop of blood. We hadn’t stopped fishing too soon. We slid into the darkening recesses of the mangroves and crossed flats and watery trails until I was hopelessly confused. Grady shut off the motor.

“Yonder’s a deep hole,” he said, “at the junction of the creek. Swing the stern around and let me try this short rod.”

I paddled for 100 yards while Ted kept up a tap routine at the mosquitoes boring through his shirt. Over his protests, Grady tied on the Candy plug and flipped it 40 feet under the limbs to where the mingling currents made an eddy. He retrieved without a strike and was flexing his muscles to lift the plug out of the water when a tremendous snook walloped it right under the bow. The collision flashed me back to the bull alligator Ted and I had jumped that morning.

I’VE SEEN some classic roping and bulldogging in my day, as well as some unforgettable conflicts with fish, but I’ve never witnessed anything like the fight Grady had with that snook. Why the brute didn’t pull the hooks out of that plug, snap the 40-pound-test line, or break one of Grady’s arms, I’ll never know. Neither fisherman nor fish gave line-not a foot of it. Around and around the boat they went, with both Ted and me dodging to stay out of the way.

I’ve no idea how the battle would have ended if the snook hadn’t decided on a last desperate bid for freedom. He threw his bulk straight into the air, missing my face by a thin scale, and landed in the boat, his tail slapping gas cans, rods, and gear like the swirl of a tornado. I dodged a plug that whistled past my ear just as Ted planted his brogans in the middle of the whole seething mess and pinned down the snook’s tail.

Grady put down the rod and took his seat as unconcerned as if he caught a 20-pound snook exactly that way every time.

Presently he cranked the motor and pushed on down the trail, while Ted and I picked lures out of the snook’s sides, belly, and fins, like we were harvesting spiny cucumbers.

The darkness closed around us, and Ted’s teeth gleamed at me out of his parched face.

“There are plenty of tricks you could try on these babies” he said, “but I never saw a more confusing one than this.”

“Than what?”

“Than feeding them candy,” he said. “What else?”

This text has been minimally edited to meet contemporary standards. Read more OL+ stories.