At first, it’s a subtle tug. A nibble, really. With a quick strip set, the line goes tight and the dark water roils as a prehistoric air-breather erupts. The fish makes a few more tarpon-like leaps and then bulldogs its way into cover just like a bass would.

Anyone who’s brought a bowfin to hand deep in Georgia swamp knows these fish are underrated. Most anglers visiting the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, which straddles the Florida-Georgia line, are interested in panfish species like flyers and warmouth. Some chase chain pickerel and others go deep for catfish. In doing so, they overlook the most dependable fly-rod target that swims in the nation’s largest remaining blackwater swamp. Also known as “mudfish” or “cypress trout,” bowfin are as unique and wild as the places they call home.

“People want to see things that they’ve never seen before when they visit the Okefenokee,” says J.D. Corbett, a 75-year-old local who knows this swamp better than anyone else alive. “And most people have never seen a bowfin.”

The Okefenokee’s vast network of swamps and shallow lakes gives anglers seemingly endless water to explore, Corbett explains. The 438,000-acre wildlife refuge features plenty of access points for canoes and kayaks. For those willing to put in the effort (and to tolerate the roughly 12,000 to 15,000 alligators that live here at any given time), 20-fish days are entirely possible. But Corbett worries this might not always be the case.

This is because the state of Georgia is currently considering a large-scale mining proposal that could jeopardize the one resource that everything in this ecosystem revolves around: fresh water.

A Proposed Mine at the Okenfenokee’s Boundary

Corbett came home from Vietnam in 1967 with a moderate to severe case of PTSD that went undiagnosed through the 1970s. The swamp was the only place where could find the peace he needed to get by.

“It was healing for me,” he says. “I built a little lean-to on the upper Suwannee River and found a place where I could just dump everything and kind of get lost for a while. If I hadn’t come to the swamp, I’m not sure I’d be here today.”

Corbett’s retreat into the swamp in the early 1980s eventually awarded him legendary status in the region. Over the years, he’s introduced hundreds of newcomers to the swamp. He used to work for the Refuge, helping clear water trails and building many of the Okefenokee’s backcountry “hammocks,” or floating platforms used for camping. Now he volunteers to keep those trails open and the hammocks in good repair.

He still fishes the swamp, and he says it might be the best place in the country to reliably target big-shouldered bowfin year-round. But these days, he spends more time worrying about the future of the Okefenokee than he does casting a line.

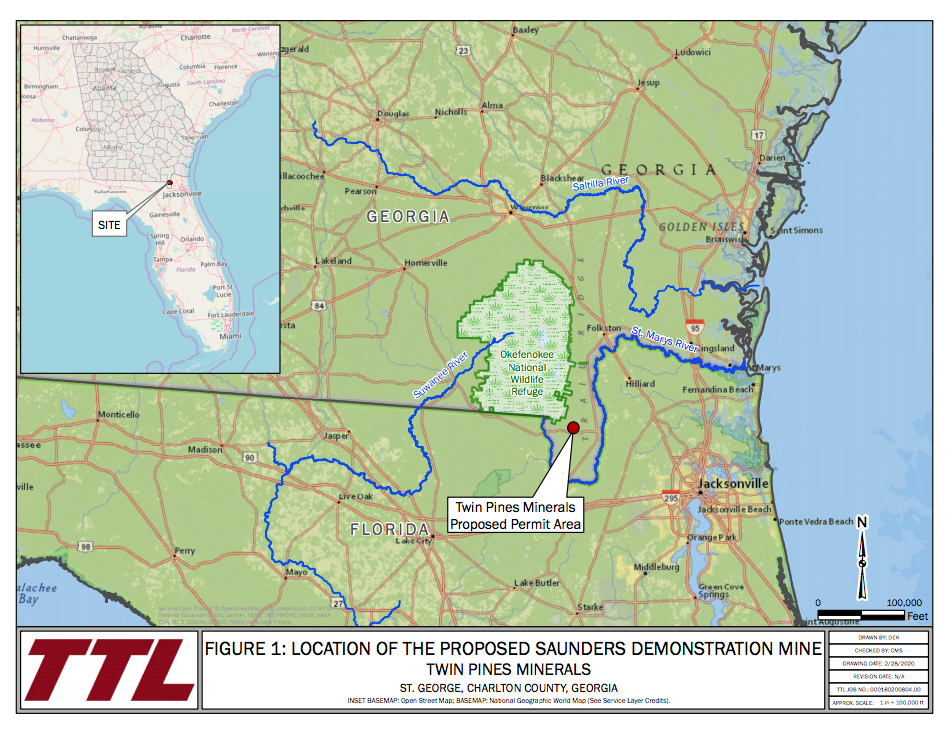

In 2017, Twin Pines Minerals, LLC, an Alabama-based mining company, announced plans to mine for heavy minerals along Trail Ridge, an ancient sand ridge that effectively serves as the eastern boundary of the Okefenokee Swamp.

Think of the Okefenokee as a giant rain barrel. It is the wellspring of two great American rivers that flow from two “spouts” on either side of the barrel. The fabled Suwannee River flows west and, after picking up a host of other blackwater rivers, it empties into the Gulf of Mexico just below the crook in the Florida Peninsula. The St. Marys River exits the swamp’s southeast corner, not far from where Twin Pines wants to mine, and continues on to the Atlantic.

Almost 2 million years ago, Trail Ridge was one of several low-lying barrier islands in the Atlantic. Today, it’s a modest terrace in the pine woods of south Georgia and north Florida, and it’s laden with important heavy minerals, like titanium and zirconium. Twin Pines wants to mine about 600 total acres of Trail Ridge.

The company claims the heavy minerals can be pulled from the ground and that the mining site can be successfully reclaimed without permanently impacting the region’s hydrology. It points out that Trail Ridge has been successfully mined, off and on, since the late 1940s, although most of this activity has occurred farther south, near the community of Starke, Florida.

Corbett knows this local history. Still he asks, the worry plain in his voice: “If you take something out, what are you going to replace it with?”

A Temporarily ‘Dirty and Ugly’ Process

In order to reach these minerals, Twin Metals would first strip the land of all vegetation, including the large pine trees that dominate the sand ridges in the region. The water table is shallow here (only 50 feet below the ridge in places), so the top layer of soil would be pushed to the sides to create a barrier that would keep water produced during the mining process on site.

The idea is to expose the white sand that was once the ocean floor. This sand holds the marketable minerals like zirconium and titanium dioxide, which show up as gray or black grains amid the white. After passing through a spiral separator, the desirable minerals sink down and the lighter sand rises to the surface. The lighter material is then used to refill the holes left in the ridge.

In order to do all this as expediently as possible, Twin Pines would use what’s called a dragline excavator—essentially a huge shovel that is pulled along the ground by a series of cables.

James Renner is the environmental stewardship manager for Chemours, a mining company that has active heavy mineral sand mines in the region (though not actively on Trail Ridge). He notes that the use of a dragline isn’t all that unusual, although his company uses a different type of large-scale excavator instead.

“It’s all about efficiency,” Renner says. “In order to be successful as a mine, efficiency is important.”

Renner declined to offer an opinion on the use of a dragline by Twin Pines, saying the company chose that option based on its own research. In fact, Renner declined to comment on Twin Pines’ mining plan at all, saying he could only reasonably comment on Chemours mining projects because he’s familiar with how his company operates. But he did agree that the process of getting at these desired minerals can be unsightly.

“Yes, it’s a dirty and ugly process, but it’s temporary. When we mine new holes, we use the same sand that’s taken out and fill those holes with it. We recycle the water that comes from the mine site and when we’re done, we reclaim the site and replant the pines or do whatever the landowner wants us to do.”

Renner says that his company has not witnessed any significant impacts to the wetlands adjacent to Chemours mining projects. He acknowledges the water table does decline a bit during the process, but the company’s data shows the water table rising and returning to acceptable levels post-mining.

Twin Pines declined to comment on its plans to mine the region. Its public relations company in Atlanta simply stated that Twin Pines was staying mum while the permitting process plays out.

Who’s in Charge?

Twin Pines’ permit application is currently under public scrutiny. A 60-day public comment period that began on Jan. 20 ends on March 20, and anyone can submit a comment to the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, which, as of last fall, is the agency responsible for issuing the permit. As of March 9, EPD had received nearly 50,000 public comments. (To submit a comment, email [email protected].)

“And we received more than 26,000 comments before we even opened the comment period, so that number will most certainly be higher,” says Sara Lips, communications director for GEPD. Lips said it could take weeks or even months to analyze the comments and draft a document that responds to concerns. There’s no timetable for the EPD to award a permit. If it happens, she says, it won’t be until all the information at hand has been analyzed.

But the EPD hasn’t always been in charge. Oversight of the permitting process has been confusing: In the last six years, the lead agency in charge of permitting has changed several times , shifting from the EPD to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to the U.S. Army of Corps of Engineers and now, after Twin Pines filed a lawsuit over jurisdiction, back to the state. The Okenfenokee is currently protected under the Biden administration’s recent Waters of the United States Rule, but one environmental study conducted by University of Georgia professor Rhett Jackson and other researchers points out that mine permitting should hinge on how the Clean Water Act is applied. The rub is that with all the agencies involved to date, and with the CWA under constant scrutiny, what will that application even look like?

Water Quality Is King

The mining application has mobilized Southern conservation academia. And on Feb. 20, a host of professors from southern universities asserted that the EPD is using the wrong water measurement gauge to determine impacts to river flows in the St. Marys from the prospective mine. Later that month, roughly 90 university professors, researchers, hydrologists, and water resource professionals from around the South penned an open letter claiming that mining beneath Trail Ridge could be disastrous for the swamp.

“Digging up Trail Ridge and then replacing it post mining will mix the existing layered sands, clays, and organic matter,” the letter reads. “This makes Trail Ridge more porous and thus more conductive to water, lessening its ability to hold water. This will alter groundwater flows through Trail Ridge and possibly lead to permanently lower water levels in the [Okefenokee] Swamp.”

The U.S. Department of Interior, which oversees management of the swamp through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, openly opposes Twin Pines’ plans. Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland specifically asked Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp to keep EPD from moving ahead with the proposed mine.

“The Department has a profound interest in protecting the health and integrity of the swamp ecosystem,” Haaland wrote. “Home to the refuge, it is a unique wetland ecosystem unlike any other found in North America and is one of the world’s most hydrologically intact freshwater ecosystems.” Kemp has not responded to the letter, and his office referred all inquiries to the EPD.

The DOI also fears that by disturbing the water table beneath Trail Ridge (and well below the elevation of the swamp itself), Twin Pines will affect the regional hydrology and pull water away from the Okefenokee. While Twin Pines’ website declares that “mining activities will not impact the Okefenokee Swamp,” there’s no independent research confirming this.

And if the water is pulled from the swamp, the impacts could reach far beyond the Okefenokee’s boundaries.

Emily Floore, executive director of St. Marys Riverkeeper, worries that mining could cause the water levels in the St. Marys River to drop so much that it could render much of the upper river unnavigable.

The St. Marys is a classic blackwater river. Lined by oak and cypress, its bottom is that same white sand that makes up Trail Ridge. Anglers access the river to chase panfish, pickerel, and bass. Farther downstream, in the tidal zone, it’s home to rare Atlantic sturgeon, along with typical inshore species, like redfish, spotted sea trout and sheepshead.

“Our biggest concern is water flow,” Floore says. “We already have flow issues now. If we lose water, the river could be in real trouble.”

Of particular concern to Floore is the glaring fact that Twin Pines has never actually constructed a heavy-mineral mine before. To have the company use her backyard for its first try is troubling.

“Do we want to be the guinea pig for this company?” she asks. “That’s a lot to ask of us from a company that has no experience with this region.”

Back in the Swamp

Corbett has had at least one lifetime’s worth of adventures in the Okefenokee. Once, while clearing a water trail, he and a fellow refuge employee had to abandon their boat and leap into the gator-infested swamp to avoid being chewed raw by a swarm of raiding fire ants. Another time, while working on a backcountry hammock, he came face to face with an aggressive black bear. He was able to chase it off by throwing his life jacket at it.

Like many old-school Southerners, Corbett also looks at politicians with a skeptical eye. He points to Kemp’s inaction on the issue, and he wonders how the proposal has even gotten this far.

“I have no faith in the politicians,” he says. “They’re not going to make the right decision. They talk all about protecting the resources and protecting the Okefenokee Swamp, and then they get behind closed doors and it’s another story altogether.”

There is some political support for Corbett’s position on the mine. Georgia State Rep. Darlene Taylor, a Republican from Thomasville, introduced a bill in January with bipartisan support in the state House of Representatives. The bill would have blocked new mining proposals around the Okefenokee, but State Rep. Lynn Smith (R-Newnan), who chairs the House Natural Resource and Environment Committee, effectively killed the bill by letting it die in committee last week.

From Corbett’s perspective, the stakes are just too risky. Either we protect the swamp’s water source, or everything in the swamp falls apart.

“They need to leave the protected area alone, and that means leaving the water table alone,” he says. “If they change the water levels, everything else will change. The lakes will begin to fill in with cypress and vegetation and then this place is lost to us.”

For anglers who love to fish the swamp, alligators and all, it’s a one-of-a-kind resource. There are other blackwater swamps in the United States, but none are as big or as biologically diverse. And while one man fly fishing for bowfin among the swamp’s cypress knees and lily pads might not ever register on the economic scale, the collective impact of fishermen certainly do. The Georgia Conservancy estimates that half a million visitors come to the swamp every year, bringing another $88 million to the Okefenokee annually. That includes roughly $64 million from recreational fishing according to the USFWS.

As for the short-term economic benefits of mining in the area, Renner says Chemours employs about 400 people locally. Twin Pines’s website, meanwhile, says that if the project is approved, the company will employ about 400 people in the area, from base laborers to laboratory technicians. The company claims its total capital investment in the region will be about $300 million.

“You don’t need experience. You don’t need a diploma. We’ll train you,” Renner says of Chemours’ hiring policies. “You’ll get a 401k and health insurance. For us, it’s about community prosperity.”

For Corbett, however, the long-term prosperity of the surrounding community hinges on a healthy Okefenokee.

“There’s no other place like this anywhere else in the world,” Corbett says. “I go and I dump all my cares out and forget about them. For a little while, I can be free. That’s what I call living.”