FOR ME, flying and fly-fishing both began in California. The first flight was as a passenger with Frank Hawks, the first fishing as a novice in the Sierras.

Then—also on the West Coast, and also in the dark ages of longer ago than I like to remember—a pilot named John Montijo taught me to fly. My husband, not so long ago, undertook some post-graduate instruction in fishing. Whether or not I’m a good flyer is debatable. Whether or not I’m a finished fisherman, isn’t. I’m not.

It’s unwise, I suppose, to be married to one’s instructor. The relationship is apt to cramp one’s style-both ways. The “severest critic” serves a purpose, but sometimes the S. C. isn’t wanted at the elbow when the student is trying to master the intricacies of casting a fly against the wind—or, for that matter, with the wind, because of that odd habit the back-cast has, under such circumstances, of enshrouding the caster in an unhappy tangle of line and leader and flies.

“Now,” I can hear my husband admonish, “drop your fly there—the dark eddy by that rock.’

In the particular pool before me there are several dark eddies and any number of rocks. Not that the exact locality makes much difference anyway because I’m not yet able to persuade my line to go where I wish it to.

“Not there. There!”

The Coachman and Professor (I can actually recognize a half-dozen different flies) drift down in quite the wrong direction. Even I realize it, just as I know they shouldn’t drift at all—they ought to go out from my rod tip straight and smart, landing ever so sweetly on the surface, and forthwith flit alluringly upstream toward me.

“Holy Cats!”… the Lord and Master-Fisherman is becoming apoplectic. “Let the line run out! Keep the tip up … gently … give the trout a chance. Now, try another cast.”

I do.

“Hellsbells! That’s not a flail—that’s a rod-only four ounces of delicate bamboo. Forget the main strength. Just your wrist—a little forearm.”

So it goes. I am conscious of some improvement. Gradually the knack of handling rod, line, reel, and flies comes with practice-comes sufficiently, at least, so that there’s fun in fishing, however far the technique may be from the perfection of experience.

“After all,” … it’s only human to talk back when my husband complains too bitterly because I’ve snapped the light leader on a promising trout … “after all, what do you know about taking an airplane off a small field?”

“Or a large one!” His grin is disarming. He’s always declared that one pilot is enough in any family. He refuses to try to learn the first thing about handling the controls, satisfied to qualify as a pretty good passenger. “Aviation,” he expounds, “is a means of going places, fast. Trout fishing hasn’t any practical virtues—unless you count frayed patience, wet feet, exhaustion, and odds and ends like mosquitoes and black flies. The queer part of it is the whole thing somehow adds up to more fun than you can get ’most any other way.”

Of course, he is an addict. I can take it or leave it.

For me the charm, I think lies not nearly as much in the fishing itself as the way it’s done, with whom it’s done, and where. Take Wyoming, for instance.

A recent migration of ours thither is chargeable to Carl Dunrud, whose comfortable, hospitable Double Dee Ranch sprawls along a high valley in the region south of Cody and east of Yellowstone Park. Carl is a cowboy whom my husband first met in Montana years ago. Since then they have had many trips on the trail together, one leading all the way to Greenland. Although Carl up to that time had never seen salt water, he proved himself as competent a sailor as he is a bronc rider. We have a souvenir of that northern trek in our home at Rye, N.Y. It is the hide of a polar bear Carl lassoed in the icy waters of Baffin Bay.

“Wrangling dudes or wrangling bears? Which is easier?” Carl turned my question over in his mind. Finally he allowed that each occupation offers its problems. “Perhaps,” he added, “the bears were more fun!”

WE WERE SITTING on the sky-line shoulder of an 11,000-foot peak, looking down on Carl’s own metropolis, the ghost mining city of Kirwin, which forty years ago teemed with activity. A million dollars was spent there before miners and backers, reaching the conclusion that getting the gold cost more than it was worth, abandoned the entire project.

Carl and I had just been discussing the progressive shrinking of our continent. Not that North America was disappearing, but only that geography wasn’t what it used to be on account of aviation. Thanks to modern flying, Wyoming has come to be almost next door to New York, in terms of the time it takes to get there.

Carl was demonstrating with a map and schedule of one of the trans-continental air transport companies.

“You can leave New York one evening and be at my ranch by sundown the next day,” he explained. “Ride from Newark to Cheyenne, transfer there in the morning, fly to Sheridan, and I pick you up there by car.”

“Or one could fly directly to Cody,” I offered. “The CWA has made the field adequate, hasn’t it?”

“Good enough for anyone, they tell me. But better still, couldn’t you land on one of these bald mountains? There are likely places up there,” he indicated the adjacent region, which looked from where we sat as if it were set on edge. “Take Meadow Creek, for instance—there’s a flat as big as all outdoors up at the head of it by the divide … ”

“How high?”

“Oh, about 12,000 feet.”

Carl was disappointed to learn that two miles up was pretty high for either landing or taking off at all times.

Nevertheless, we decided that perhaps I actually could get within a few miles of the Double Dee with my plane—though how I could safely leave the poor creature perched up on a highland sheep range, and whether I could get her off again, were questions open to debate.

At all events, the Yellowstone Park region, tucked into the northwestern corner of Wyoming, may be but a day’s journey from the eastern seaboard for modern vacationists. This time Mr. Putnam and I drove, instead of flying. Habitually we commute across the continent by air, but we chose to make this vacation trip, for variety’s sake, by road.

An interesting land voyage it may be. This year a pleasant contrast to some other journeys was the comparative optimism of the communities encountered throughout the eleven states traversed. Every garage, service station, hotel, and wayside merchant we queried reported his business the best it had been in four years. Nowadays Americans seem to be seeing America, said our highway friends.

The dark side of the picture is the plight of the drought-stricken regions. Only some of this we saw, but enough to make us heartsick—saharas of dust where should have stood green grain; dried-up rivers and waterholes; corn shrivelling on wilting stalks; gaunt cattle without drink or food; discouraged farms and deserted homesteads. Though we saw only the fringes of it, obviously a far-flung calamity will add heavy burdens for all of us, in one way or another.

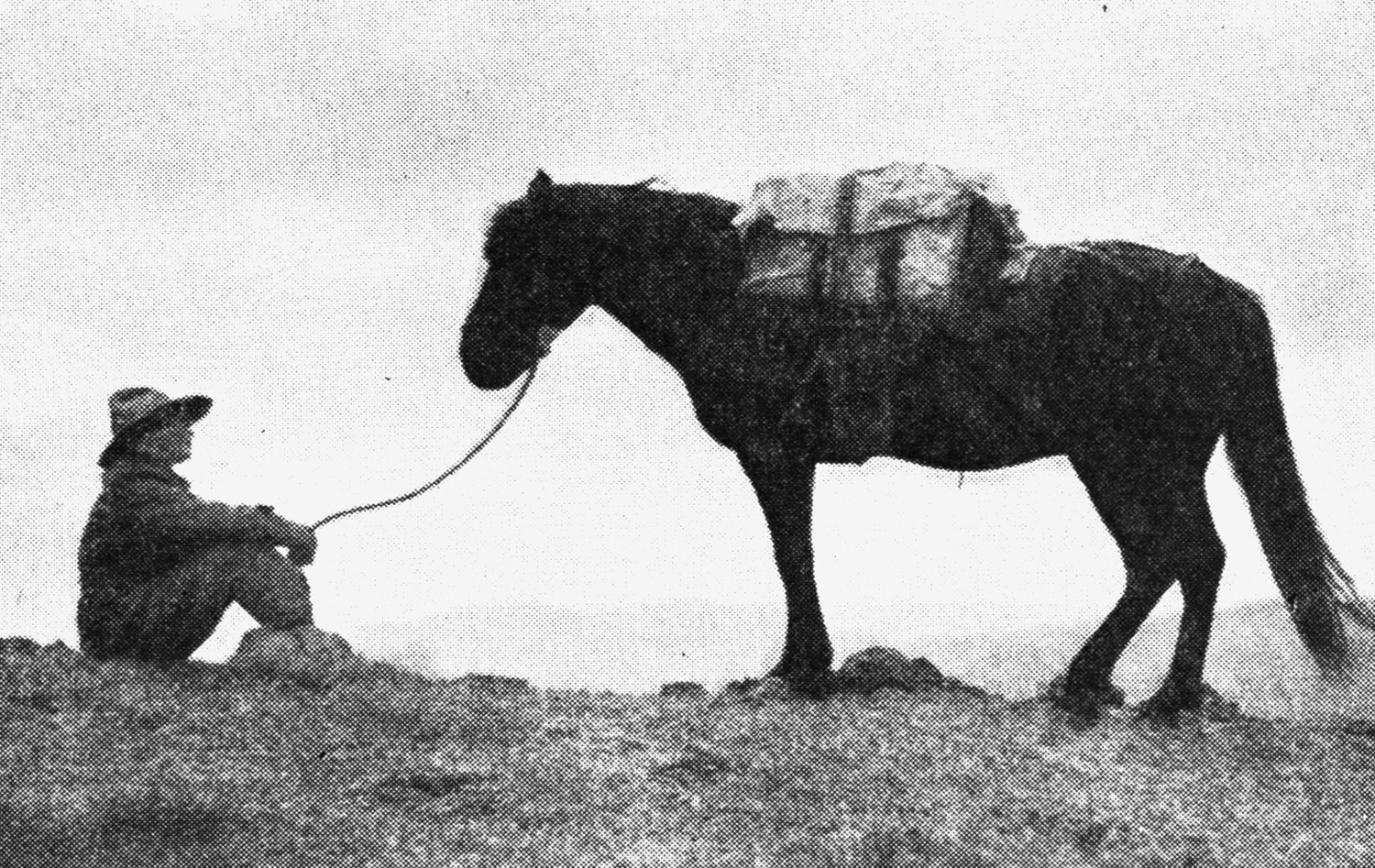

In happy contrast to the dusty despairs of drought and the worries of a bewildered world was the crisp peacefulness of the Wyoming mountains with all the needs of living right at hand on the pack horses, a concentrated world of one’s very own, refreshing, restful, and remote.

The first time I flew the Atlantic, with Wilmer Stultz and Slim Gordon, back in 1928, we were stranded at Trespassey [sic] up in Newfoundland for thirteen days, waiting for favorable weather. During that stay the prime delicacy of the local larders turned out to be rabbit, appetizing on occasion but wearisome if seen too often.

Which is one reason why I turned to trout. In the neighboring streams I saw more of them than I have seen before or since; mostly little fellows, to be sure, but so many it was simply a matter of dropping in a hook and pulling out a fish. However, trout fishing did not interest the natives. Cod were easier to get, I suppose.

On our pack trip with Carl, fishing was only a part; doing nothing was really the object. In this endeavor we aimed at being neither too luxurious nor too primitive. Our equipment contained a cook tent, with a stove which folded up magically. Other appurtenances of soft living were a folding chair and table. Beyond that everything was of the simplest. After all, for comfort there’s nothing one needs on summer trails beside a sleeping bag and a tent just big enough to shed night rains—ordinary daytime showers dry quickly as one goes.

At the Double Dee ranch itself there are the best of beds and other amenities, ranging from a telephone to a porcelain bathtub with running hot water that actually runs. And welcome both may be at the end of a week or two in the hills.

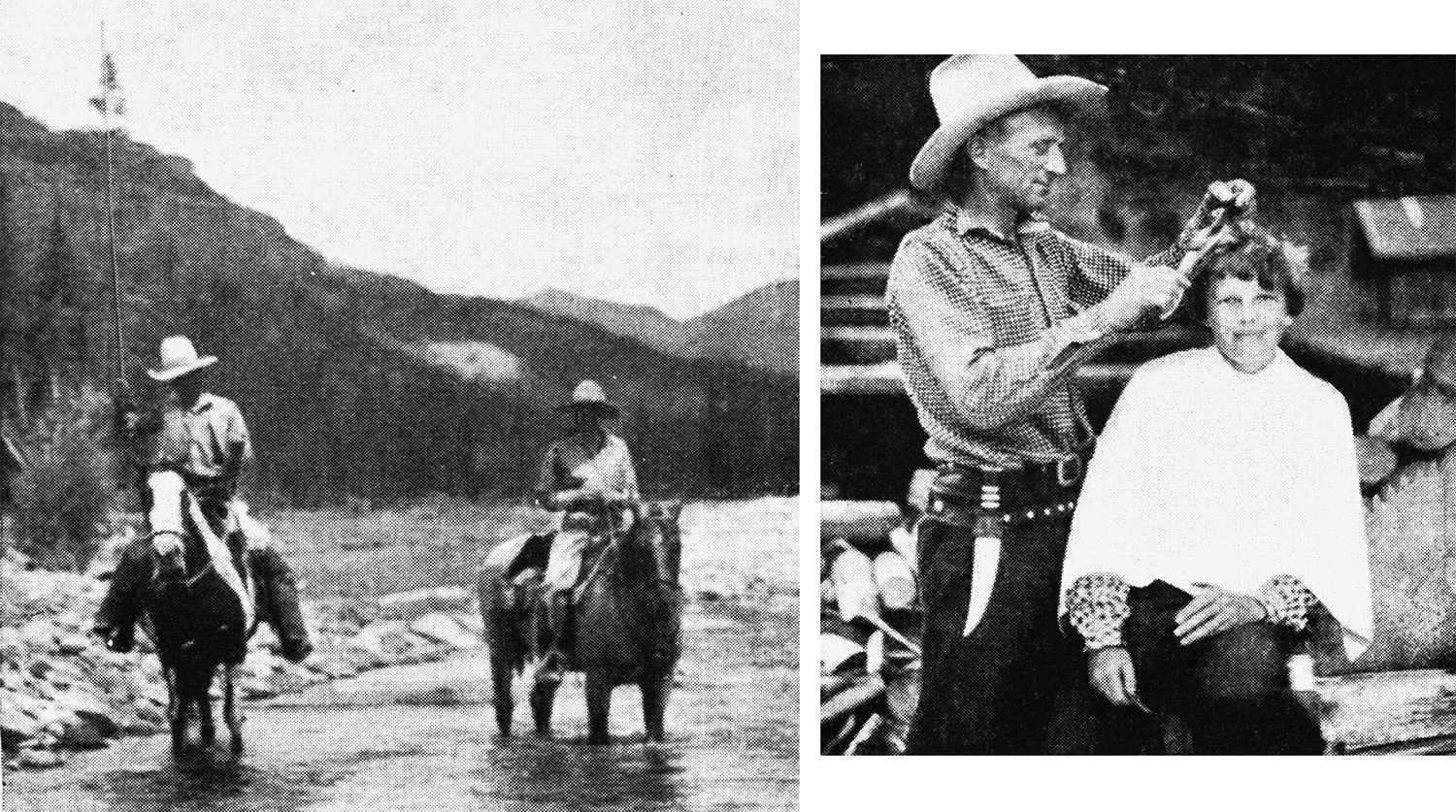

Our locomotion was chiefly on horseback. We added a fillip to just riding, however, for on fishing trips we found no great difficulty in fly-fishing from horseback. That is, after I’d mastered the rudiments of the art—for my steed, a supremely wise strawberry roan named Red, was at best unenthusiastic about my wielding a rod from the saddle, and quite actively objected when the fish carried the line in the vicinity of his legs.

We indulged in our equine fishing on Frontier Creek where the stream loafs along the flat reaches of a valley paved with rounded stones and pebbles. In that kind of going one has to ford the stream many times, and it was pleasantly convenient to stay in the saddle and let the horses do the wading.

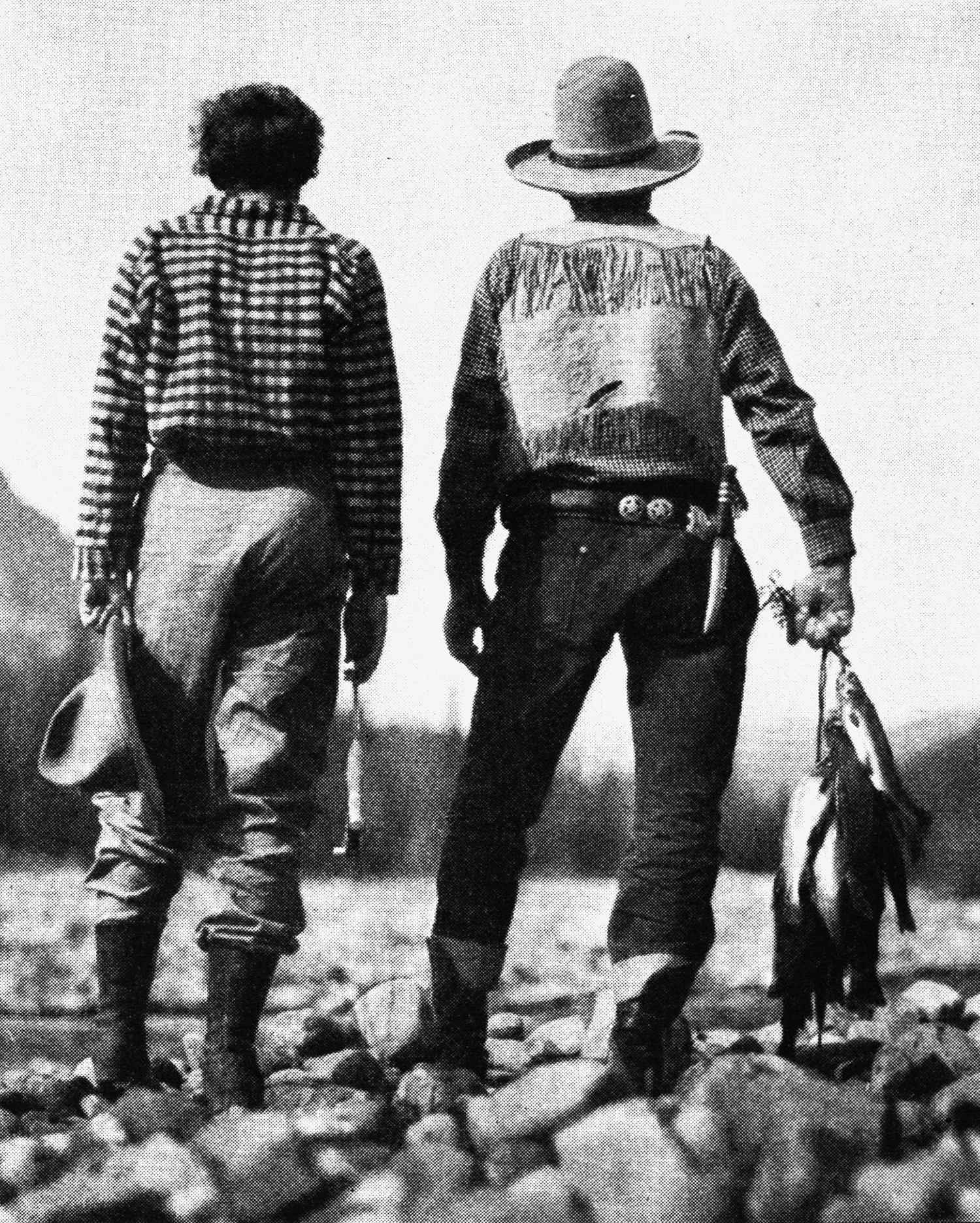

It was amusing, also, to cast from midstream to the pool below and no great trick to hook fish that way, although more difficult to land them without dismounting. As a matter of prestige G. P. and Carl both contrived to bring hooked fish alongside their mounts, who patiently stood by while their riders accomplished the ticklish process of bending down to the water’s surface with one hand and with the other holding the rod aloft. I was content to let the others land mine for me, although I did have the fun of capturing two trout, quite unaided, both hooked on the same cast.

In our camp talks, after Carl had asked his share of questions regarding women flyers, I sought his reactions as to women anglers. He said there were some good ones but many of those he knew lacked experience.

“They’re getting it now,” I said. “Recent statistics show a great increase in the number of licenses issued to women.”

“The poor fish,” observed Carl.

“Mrs. Martin Johnson,” I continued, ignoring the ambiguity, “catches all the fish needed for food on the African expeditions with her husband. And that’s the only way to fish,” I added challengingly, “or hunt.”

Of course a discussion on the pros and cons of killing wild life immediately rocked the party. I held out, as always, against killing for killing’s sake. To acquire food, to protect property or livestock, or to provide museums with specimens for scientific purposes, seem to me to be the only possible justification for slaughter. Even those excuses should be controlled, even more than they are today, lest animals face extinction on one count or another. The basic principle of which applies to fishing, even though fish are reasonably easy to replace.

To draw more fire I remarked I’d catch my food in still, deep waters with baited hook. One can think better. Whole days can be dedicated to fish and philosophy, with the surprise element never absent—for who knows what will become ensnared on the end of the line, or what noble idea may be born in the head.

“The latter likelihood is remote in the type of fishermen who prefer still water,” began my husband.

But just then the sudden appearance of a band of elk against the sky line of a ridge across the valley from camp terminated the discussion. Which perhaps was well, for after all my experience with fishing of most kinds is too limited to qualify me in a piscatorial debate. To broach the heresy of using live bait to a dyed-in-the-feather fly-fisherman, or to expound the satisfaction of still water as compared to the joys of following the ever-changing face of streams, was to risk vacation happiness. Words cannot settle such cosmic arguments. Comparisons are as fruitless as those in the world of aviation when the merits of heavier- and lighter-than-air-craft are battled over.

But when the arguments are ended, and the camp fire faded to dull embers, it is fun, lying snugly in the sleeping bag, to plan the next pack trip. In the air, of course—not with horses. Such a pack-plane trip I hope some day to make, with everything in the fuselage—tents, bedding, food, the same self-containment as the microcosm of the pack train.

This story originally ran in the December 1934 issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.