Los Angeles is known as a global capital of automotive culture, a germinating point for trends set amid ubiquitous superhighways and their crushing smog and traffic. But how and why did L.A. become a city of cars? A deeply researched and richly illustrated new book, Driving Force: Automobiles and the New American City 1900–1930 (Angel City Press, $50) by Darryl Holter and Stephen Gee seeks to answer these questions.

Holter posits that a combination of key factors catalyzed the why of L.A.’s vehicular obsession. Unlike New York or Chicago, the brunt of L.A.’s colonization by Europeans, and industrialization, began late in the 19th century, contemporaneous with the automobile’s development. “Both came of age at the same time, they sort of grew up together and their relationship was intertwined,” Holter explains.

The sunny climate allowed cars to be used year-round, a boon and a unique market attribute in the car’s early years before roofs or paved roads. And, unlike in New York or Chicago, where trains traverse the city as well as commute to the periphery, the fixed rail system in L.A. was set up mainly to move people back and forth from work in the center to residences in the suburbs. The car offered freedom for intracity travel.

The mountainous topography of Los Angeles, and the residential and commercial development of it, also lent itself to the car and vice versa. “The automobile allowed people to go farther away from the center, higher into the hills, closer to the desert, closer to the ocean,” Holter explains. “And that, of course, meant that real estate could be developed there.”

The nascent film industry was able to use automobiles to scout and shoot (and star) in the varied locales—urban, suburban, rural, mountainous, seaside, riverside, desert, ranch—within easy reach of the city. And the advent of the car meant that filmmakers and actors no longer needed to carry their equipment or wear their costumes on the train or streetcars, a liberating shift in production scale. “Hollywood made the car, and the car made Hollywood,” Holter says.

The Local Dealer Was Crucial

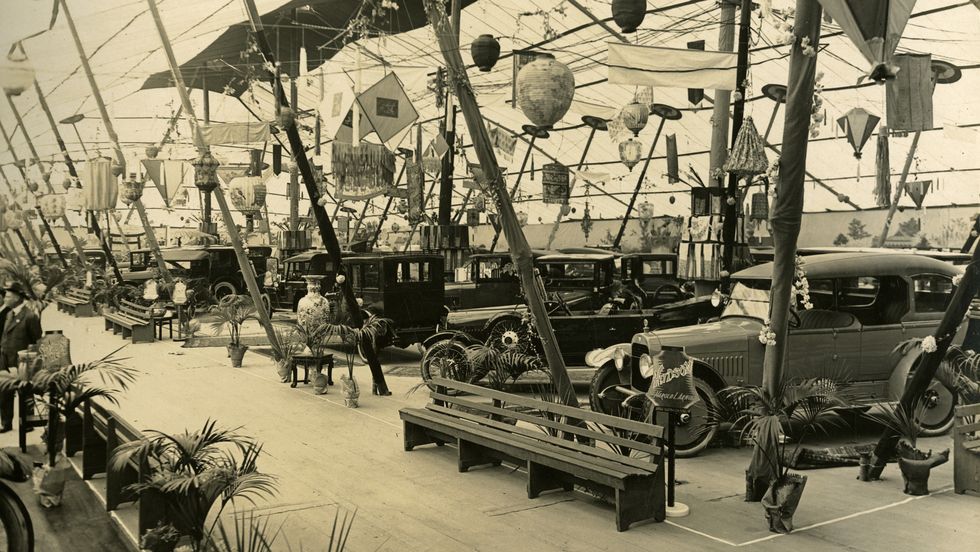

But the core focus of the book is on how L.A. became the epicenter of the automotive market. Holter attributes that to one core notion. “It was these really local entrepreneurs, bankers and car dealers, local risk takers, who provided the critical link between the carmakers and buyers,” he says. “It was the dealers who found ways, through trial and error, to put people behind the wheel, and eventually convinced them that the car was a necessity and not just a luxury.”

These innovations included many still in practice today. Primary among these were the independent car dealership franchise, the used-car market, and dealer-sponsored service centers. But perhaps the most profound was the idea of hard goods financing: making a large purchase like this on credit. Prior to the car, the notion of an accessible and increasingly necessary category of commercial good—one within reach of the common person, but which couldn’t readily be purchased outright—didn’t exist.

“Neither the factories nor the banks or the finance companies offered retail credit in these early years. So the dealers, because they wanted to sell cars on their own, started to experiment with paying on running credit by accepting down payments and promissory notes,” Holter says.

Even more intriguing is the confluence Holter uncovers between these retail establishments and the early broadcast industry. L.A. dealers were among the first owners of local radio stations such as KFI and KNX. “These stations were launched primarily as a way of selling cars,” Holter says. The motivation was financial, but also temperamental. “These dealers became wealthy so quickly that they were seeking the next groundbreaking technology, looking for the next investment,” Holter says. “That’s the type of entrepreneurs they were.”

Holter believes that the book has profound contemporary relevance, as consumers and automakers debate the validity of the franchise dealer system. “I think that some of the same factors that caused direct sales approaches to fail more than a century ago may still prevent high volume manufacturers from really being able to go totally direct,” he says.

According to Holter, these include human-to-human contact in sales and negotiations, as well as protocols for delivery and repairs. “Things like that,” he says, “I don’t think are handled well by the internet.” (We might add the unfairly privileged pricing and allocations, and other deceptive practices, that OEMs have granted to stores they own in the distant and recent past, one of the reasons for the establishment of the dealer system in the first place.)

Holter also thinks the story of the car’s emergence, and subsequent global domination, speaks to our shifting contemporary environment, and the potential for unanticipated consequences of new inventions—like functional AI. “It’s a reminder of how we have changed society and how hard it would be for people to give up those changes,” Holter says. “But it’s also a reminder that if you create the right technology at the right price, the impact can be enormous.”

Contributing Editor

Brett Berk (he/him) is a former preschool teacher and early childhood center director who spent a decade as a youth and family researcher and now covers the topics of kids and the auto industry for publications including CNN, the New York Times, Popular Mechanics and more. He has published a parenting book, The Gay Uncle’s Guide to Parenting, and since 2008 has driven and reviewed thousands of cars for Car and Driver and Road & Track, where he is contributing editor. He has also written for Architectural Digest, Billboard, ELLE Decor, Esquire, GQ, Travel + Leisure and Vanity Fair.