The Australian Government’s recently published National Electric Vehicle Strategy focuses on big-ticket issues like increasing EV supply and fleet uptake, while plugging charging infrastructure gaps.

But other issues are covered as well, based on hundreds of submissions from companies and research bodies: for example the risk of an EV-related fire involving lithium-ion batteries.

The government subsequently floated a plan to fund “world-leading guidance, EV road rescue demonstrations, and fire safety training to address safety and risk knowledge gaps around EVs, chargers and battery technology”.

While rare, spectacular footage of EV battery fires and recalls of popular EVs due to fire risks such as this one and this one have captured public attention and led to misconceptions about how common they are.

The issue of EV fires (thermal runaway events) has also caused concern for the United Firefighters Union of Australia, and led Melbourne-based charging provider JET Charge to call for national standards addressing fire safety requirements in the built environment,

One Australian company deeply involved in this space is EV FireSafe, which keeps a database of verifiable worldwide passenger EV battery fires and tracks emergency response methods that work.

The company draws funding from the Australian Department of Defence, and has been referenced by the Australian Fire Agencies Council, Fire Protection Research Foundation (US), and the National Fire Chief’s Council (UK).

We spoke with project director Emma Sutcliffe, who had just returned from a research trip to several European conferences focusing on the issues around EV fires.

“EV battery fires are very rare, but present new challenges and risks for the global emergency response community, and we’re still working out how to manage these incidents,” Ms Sutcliffe said, adding no fire agency globally had published relevant standard operating procedures.

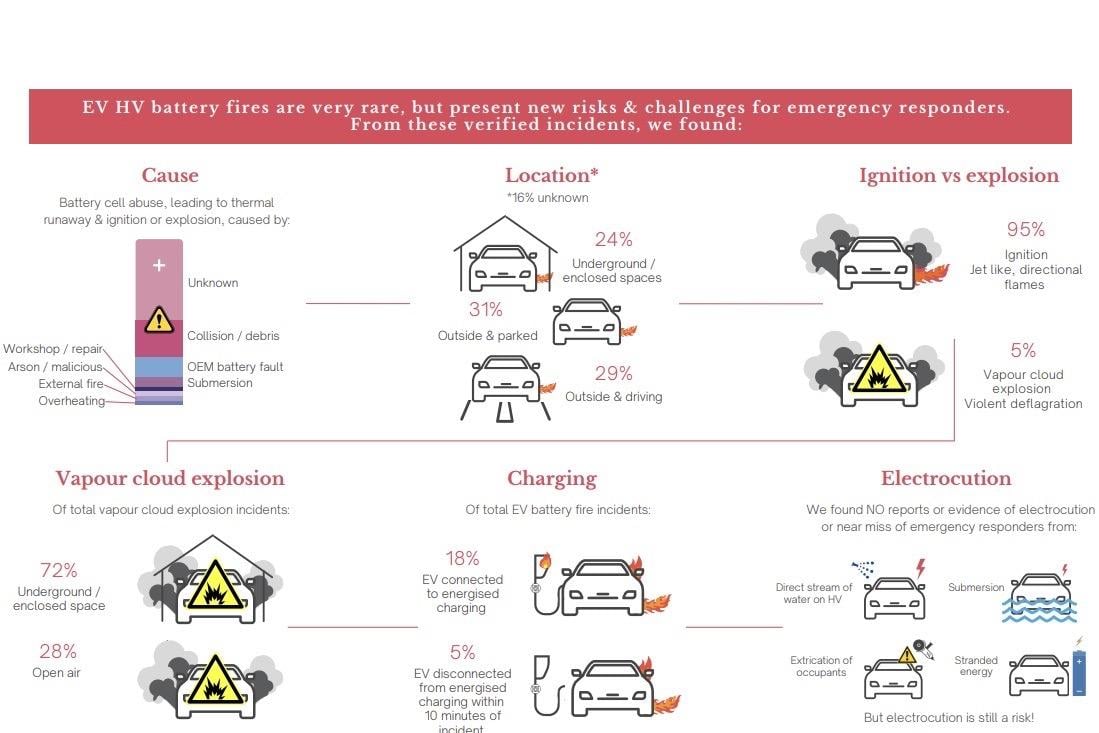

Her organisation publishes regular updates detailing its database of worldwide EV fires, with a few interesting findings as of April 30 of 2023 including:

- EV FireSafe has verified 375 EV traction battery fires and is investigating a further 87. To give this context, more than 10 million electric cars were sold worldwide in 2022 according to the International Energy Agency.

- The majority of these fires occurred after 2019.

- The main causes of thermal runaway and ignition or explosion in order are collisions and debris, an OEM battery fault, water submersion, workshop error, arson, an external fire, and overheating.

- One incident describes a tow ball falling off a truck and hitting the underside of an EV, leading to battery fire.

- 95 per cent of EV battery fires were ignition events with jet-like directional flames, with the remaining 5 per cent being a vapour cloud explosion usually in an enclosed space.

- Of this set of incidents, 31 per cent were of cars parked outside, 29 per cent were cars driving outside, 24 per cent were in an enclosed space, and 16 per cent were unknown.

- Only 18 per cent of total EV battery fire incidents took place while the car was connected to a charger, with a further 5 per cent disconnected from the charger within 10 minutes of the fire.

“… EVs are far less likely to catch fire than ICE [vehicles], however they’re obviously newer vehicles so we’re watching to see if that changes over time,” she cautioned.

“We work with a global network of fire and battery experts, and I particularly love that so many are willing and enthusiastic to openly share knowledge.”

Specific to Australia, Ms Sutcliffe claims “there have been only four passenger EV battery fires that we’re aware of in Australia”, three of which were parked in structures that burned down and took the EVs with them, and one that was linked to arson.

“Our real risk is light EVs – e-bikes, scooters and skateboards – which are destroying properties, killing and injuring people around the world on an almost-daily basis,” Ms Sutcliffe added.

In its submission to the National EV Strategy, EV FireSafe took aim at what it called “anti-EV sentiment being driven by mainstream and social media into emergency circles, leading responders to believe EV battery fires occur frequently, are impossible to manage and that EVs connected to charging or involved in a collision pose a high risk of electrocution”.

“This media bias is seriously impacting emergency responder confidence in EVs, and responder safety when managing incidents involving EVs. Nascent EV research and testing programs cannot yet provide all answers and need to be urgently supported,” it added.

The company has called for actions such as EV emergency response guides written to ISO 17840 standards, a national rollout of blue ‘EV’ badging, road rescue demonstrations, an emergency response guide database, online sessions for emergency agencies, and the funding of an EV training prop.

Then there’s the issue of best-practise responses, adds Ms Sutcliffe.

“Consider incident management: do we cool the battery with water which takes a long time, submerge it in a water bath which is expensive, difficult and not recommended by any EV manufacturer, or can we let it burn out and remove the stranded energy risk?” she said.

There’s also the issue of what OEMs can do, with examples in this space being Renault’s fitment of a water inlet to the battery pack. New chemistries could also help, for example the proliferation of more stable lithium iron phosphate packs in BYDs and Teslas.

According to Ms Sutcliffe, EV drivers can help keep emergency responders safer by not driving or charging their EV if:

- They’ve been involved in a collision (ring the manufacturer and get advice, she says)

- It’s been submerged in water, such as flood water

- It’s been recalled by the manufacturer

When installing home EV charging, ensure the wallbox has the RCM Tick of electrical compliance, that it’s installed to ASNZ3000 wiring rules by a qualified electrician, and check it for wear and tear regularly.

MORE ON THIS: Firefighters still struggle to defeat EV fires effectively