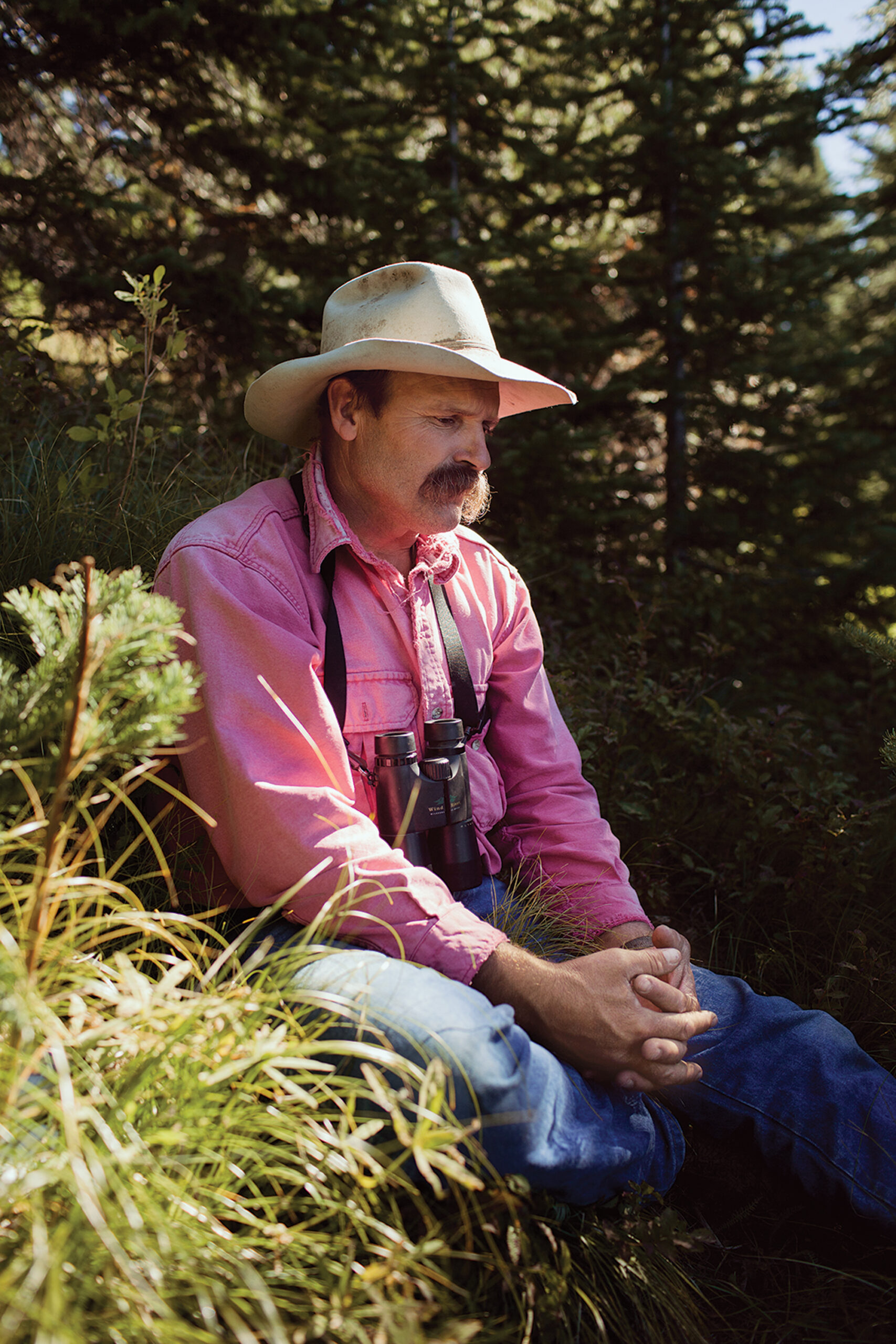

BILL BELL is sitting behind me on the ridge, just a few yards over my left shoulder. If I glance sideways, I can see his huckleberry-stained cowboy boots, but I can’t look him in the eye unless I turn all the way around. On the opposite side of the valley from us, about 600 yards away, sit Bill’s son Ty and their hunting buddy, Mike Smith.

The four of us had hiked about 3 miles into the backcountry along the Idaho-Montana line in hopes of spotting and stalking black bears out feeding on the berry-covered ridges. But as we glass Ty’s side of the valley and he glasses ours, it becomes clear that there are no bears in the area on this warm September morning.

Running out of small talk, our conversation drifts toward the days, weeks, and months that followed the bear attack that made this corner of the backcountry famous, and the reason I’m along with this group in the first place.

“I was worried about Ty, and I wanted to protect him. What bothered me about it the most was everybody criticizing him, without knowing what actually happened,” Bill says, his voice quavering with anger, which I know is partly directed at me. He’s been waiting a long time to get this off his chest.

“People were saying they would have done this or that, people who have never spent a single day in grizzly country,” he says. “Then the Outdoor Life story “Fatal Adventures,” March 2013 came out saying he should have ‘shot like a sniper.’ Ridiculous. Most guys wouldn’t do half as well as Ty in that situation.”

I just nod my head and look at Ty in the distance. He’s a big, solid guy with a gentle-giant disposition and soft features that make him seem even younger than his 22 years. I imagine that if we’d gone to high school together, we would have been buddies. I hear Bill digging around in his backpack behind me and recognize the metallic clank of the Ruger .357 I had seen him wearing the previous day. He stands up behind me.

“I’m going to check the next drainage over. You just stay here for now,” he says and walks away.

The Black Grizzly

Later that day we regroup and Ty leads us deeper into the backcountry to show me exactly where the attack occurred. After a handful of switchbacks and one steep ascent, we reach the top of Scout Ridge. The only other time he’s gone through the whole story, step-by-step, was with a Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks officer after the attack.

On September 16, 2011, Ty Bell and Steve Stevenson sat on Scout Ridge to glass a wide huckleberry patch on a distant slope; British Columbia’s Purcell Mountains towered in the north. Each man had bear tags for both Montana and Idaho in his pocket. After 30 minutes, a sizable bear appeared from a draw only about 80 yards to their left (almost exactly on the Montana-Idaho state line). But just as quickly as it appeared, the bear slipped out of the draw and fed its way out of sight into a thin patch of spruce trees.

Steve and Ty quietly sidehilled to catch the bear on the other side of the trees. Steve crept low on the slope, in case the bear headed downhill, while Ty stayed high. Within a few minutes Ty spotted the bear easing out of the bush. The boar was only 60 yards away now, busily gobbling berries. With the breeze in his face, Ty watched the bear closely for a few moments to be sure that it was a black bear and not a grizzly. It had coal-black hair, and no guard hairs. As the bear continued to feed, Ty noted that there was no discernible hump in its back, nor did it have a grizzly’s telltale dished face. It was a big bear, weighing probably 400 pounds, Ty figured, but there had been bigger black bears killed in the area in recent years, so its size was not especially surprising.

Convinced it was indeed a black bear, Ty raised his father’s Winchester Model 70—a high school graduation present Bill had received in 1978—and put a 180-grain .30/06 slug into the big boar.

The bear spun and retreated into the spruce patch. Ty chambered another round and waited. Steve hustled over after hearing the shot and they stood together, rifles ready, watching the small strip of trees. They could see the tops of saplings quiver as the bear thrashed in the bush. They could hear him huffing heavily, blood gurgling in his throat. They carefully circled downhill, keeping 50 yards of open ground between themselves and the bear.

Twenty minutes or so ticked by as they waited for the bear’s death moan, but it never came. They circled back uphill to see if they could spot the bear from the other side of the spruce patch, and that’s when Ty spotted the dark, square head through the green needles about 50 yards away.

Just as Ty found black fur in his scope, the bear exploded from the thicket and headed straight for him. He fired as the bear bore down on him, Steve firing a split second after. Both bullets missed their mark, but Steve yelled after his shot and caught the wounded bear’s attention. The animal turned on a dime and, gaining downhill momentum, hit Steve waist-level at full speed. (Later, game officials told the Bells that a grizzly running downhill could reach 40 mph.) At that speed, the 400-pound bear smashed into Steve with bone-crunching force. The collision was so violent that it blew the inseams out of Steve’s pants.

The bear flipped head-over-paws, tumbling downhill with Steve in its grasp, and they crashed into heavy cover out of Ty’s view. Ty frantically yelled Steve’s name but heard no response. Rifle ready, he carefully entered the thick brush. Ty saw that the bear had Steve facedown with his arms pinned behind his back beneath the dead limbs of a large spruce. The bear was facing downhill and quartering away from Ty as it tried to scoop up Steve, who lay motionless on the ground. Ty, now only a few paces away, fired three times at the bear, dropping it on top of his hunting partner.

Out of bullets, Ty ran back up the ridge, retrieved Steve’s gun, and fired one more shot into the back of the bear’s head. Ty rolled the bear off Steve and noticed its long, blond claws. Only then did he realize that the bear was a grizzly.

Ty moved his unconscious hunting partner onto his back. He grabbed Steve’s arm to roll him over and could tell he was in bad shape. Steve’s face and lips were purple. Ty watched him draw one last ragged breath.

Ty checked for a pulse and found none. He pulled up Steve’s jacket and shirt and administered CPR, but the hunter could not be revived. Ty dashed to the top of the ridge to find cell phone service and call 911. After directing officials to his location, he stood on top of the ridge and waited for the helicopters.

“It was half panic attack and half shock,” Ty says. “I just felt so alone.”

A Mountain Memorial

By the time Ty finishes his story, we’re standing in the dark little spruce thicket where Steve died. It’s hard to imagine the buzz of helicopters circling the ridge and authorities swarming the area. Now the only noise comes from a few pine squirrels and mountain chickadees stashing away food for the winter.

Ty is trying hard to keep his composure. He had done everything he could to save his friend after the attack, and for two years the people closest to him reassured him that Steve’s death wasn’t his fault. But now, in the shadow of the big spruce, his despair is mounting.

Bill pulls a small wooden cross and a sharpie from his pocket. He writes Steve’s name on the cross and Ty sticks it on the spruce, wedging it between dead branches. We stand there staring at our boots, nobody quite sure what to say. Finally, Bill breaks the silence: “We’ll never forget you, Steve.”

We grab our guns, leave the shadows of the thicket, and hike up and over Scout Ridge in the midday sun.

Entry Wound 4

It wasn’t until the day after the attack that Ty learned it wasn’t the bear that killed Steve, but a bullet. One of the rounds Ty fired ricocheted through the bear and hit Steve in the chest. In the weeks following the attack, investigators examined both Steve’s body and the bear’s. A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report on the investigation states that there were four entry wounds in the bear: three in the chest and one in the neck. A diagram of the necropsy, conducted by Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, tells the story.

Ty’s initial shot hit the bruin behind the right front shoulder, blew through its lungs, and fragmented in the left shoulder. The entry wound through the bear’s neck was the coup de grâce Ty made with Steve’s rifle. One of the bullets fired after the bear had Steve in its grasp hit farther back in the ribs, traveled the length of the chest cavity, but never passed through. Another bullet, which created an entry wound labeled “4” on the necropsy diagram, entered at the center of the right side of the bear’s rib cage. It traveled down through the chest cavity at an angle, exiting just left of the sternum—and then hit Steve.

The report states: “The bullet removed from the dead hunter had bear and human DNA.” The report also noted that Stevenson had bite wounds on his left thigh and subsequent “drag wounds.”

The Court of Public Opinion

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office all investigated the incident, but no charges were ever brought against Ty Bell.

“It’s a horribly tragic accident,” Lincoln County Sheriff Roby Bowe told the media after the attack. “It started off with a single misjudgment and ended up in a horrific act that will affect families for a very long time.”

The United States Attorneys’ office never prosecuted Ty for illegally killing a grizzly because, according to the USFWS report, it was clear that Ty thought he was shooting a black bear.

But the media, and those who consumed its reports, were not as forgiving. Initial stories in local and national papers—from the Spokane Spokesman-Review to the New York Times—stated that the hunters were out-of-towners and implied that they might be inexperienced in the backcountry. Comments from every corner of the internet flooded the news.

“If you’re hunting black bear, and you shoot a grizzly instead…and kill your friend in the process…I see a lot of criminal negligence,” said one commenter on Opencarry.org.

“The tragedy that occurred here is due to ignorance. How can you call yourself a hunter and not know what you are shooting at?” a commenter on the Spokesman-Review site wrote.

Internet commenters hiding behind anonymous user names were not the only ones to leap to conclusions. In the March 2013 issue of this magazine, a story recounting the attack stated: “This is not the time for wild, aimless trigger work. This is when you must act like a sniper: Wait for your moment, exhale, and squeeze.”

The Real Deal

The weeks following the attack were the darkest the Bell family had ever faced. “I watched over Ty, maybe too closely,” Bill says. “But I was worried that he was going to take his own life.”

The comments and accusations cut deeply, even though they were unsubstantiated. Bill, Ty, and Steve lived in Winnemucca, Nevada, where they worked as gold miners, but Bill and Ty had lived around Bonner’s Ferry, Idaho, for most of their lives. Bill had guided bear hunters and elk hunters in the region for about 20 years, until a decline in elk numbers sunk the outfitter he worked for. Bill is a modern-day mountain man. He lead packhorse strings, logged, and rambled his way across the West. He once walked off a logging job after his boss wouldn’t give him a second week of vacation to fill an unpunched elk tag.

Bill was proud to see his son coming into his own as an outdoorsman. “If ever there was a young woodsman coming up through the ranks, it would be Ty,” Bill says. “He’s the real deal.”

Bill raised his son in the backcountry, bringing him along to elk camp from the time he was a little kid. Ty cleared trails as a part-time job, and he shot his first elk when he was 12.

Ty didn’t have the same wild streak as his father, however—he passed up an offer to guide for sheep and moose in Canada in order to hold a steady job and settle down with his wife. But his passion for hunting was nearly as strong as his father’s, and in the hard times that followed Steve’s death, it was hunting that kept Ty going.

“It was hard to tell with Ty because he wouldn’t say a lot about it…. I thought Steve’s death was going to put an end to Ty’s hunting, but it didn’t.”

Back in the Hunt

It’s the last morning of our hunt and Ty is sprinting full-tilt across the top of a ridge, hurdling boulders and huckleberry brush. For most of the trip he’s been ultra cautious—rarely straying too far from the group, carefully skirting around thick cover, his rifle always in hand, a can of bear spray fixed to his backpack’s waist belt—but now I’m struggling to keep up with him.

Bill had waved us over after he’d spotted a big black boar that was headed up another ridge across a draw. If we can cross our ridge before the boar tops his, Ty will be able to get a shot within 300 yards.

We traverse the ridge just in time to catch the boar stepping out into an opening. Bill and I examine the bear through binoculars while Ty finds a stump to rest his rifle on and gets ready to shoot. The boar has a huge, square head; a heavy, sagging belly; and a perfect, jet-black coat. We all confirm that it’s a black bear. But just as Ty is about to slide off the safety, the bear senses trouble. Four hunters scrambling around is too much commotion, too much noise. The old boar slips through the opening, into the timber, and up and over the ridge. He’s gone.

We glass a few more drainages in the afternoon but spot no more bears. As the sun starts to set, we begin the long hike back to the trailhead, Idaho to our left and Montana to our right. We move carefully through thick parts of the trail, knowing a bear—black or grizzly—could be around any corner. After a few miles of silence, Ty perks up. “Next year we should get bear tags in Montana, too. That way we can hunt both sides of the line.”

Bill just smiles.

This story, Return to Scout Ridge, originally appeared in the September 2014 issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.