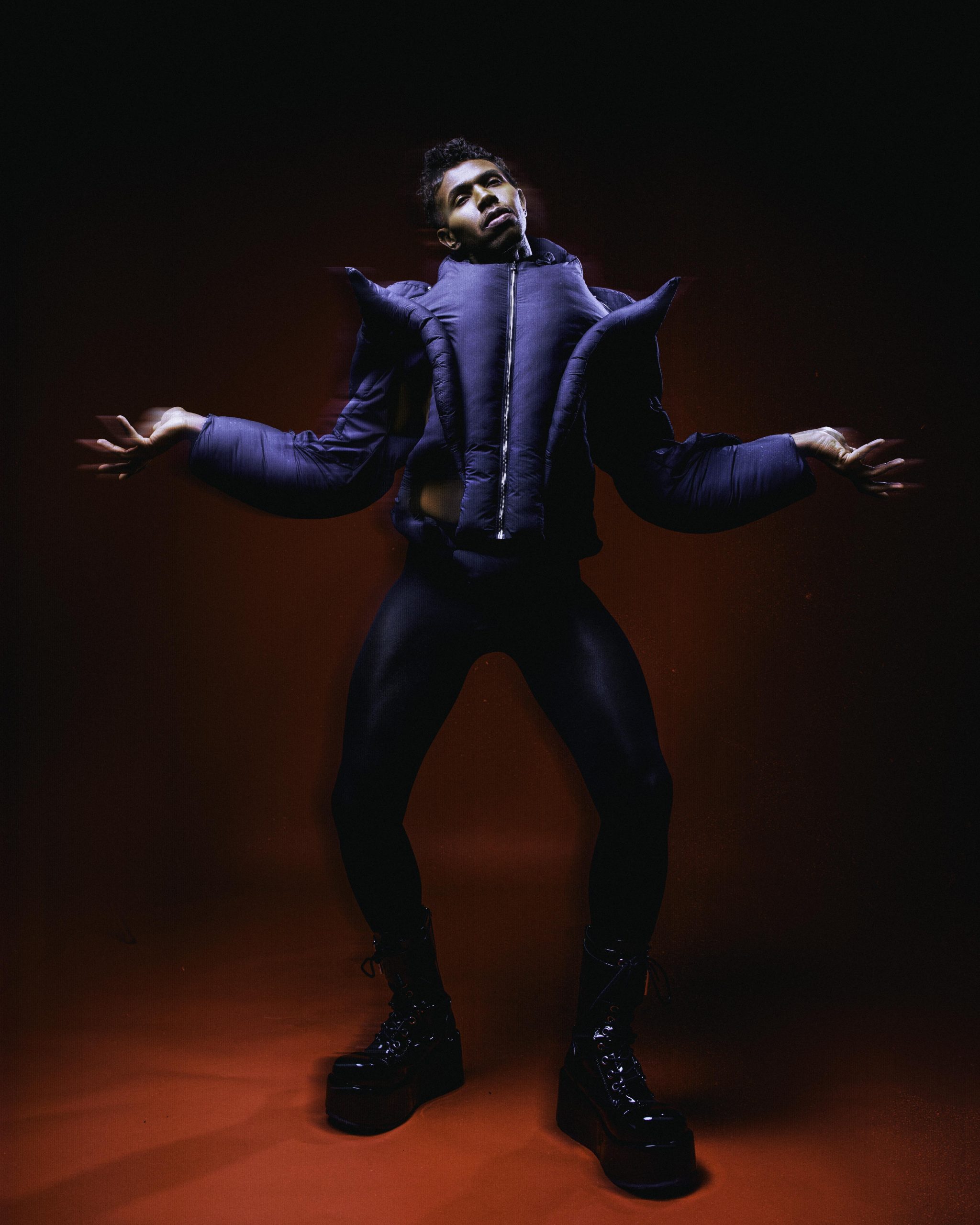

Story // JoAnn Zhang

Photographer // Hope Glassel

Stylist // Mateo Palacio

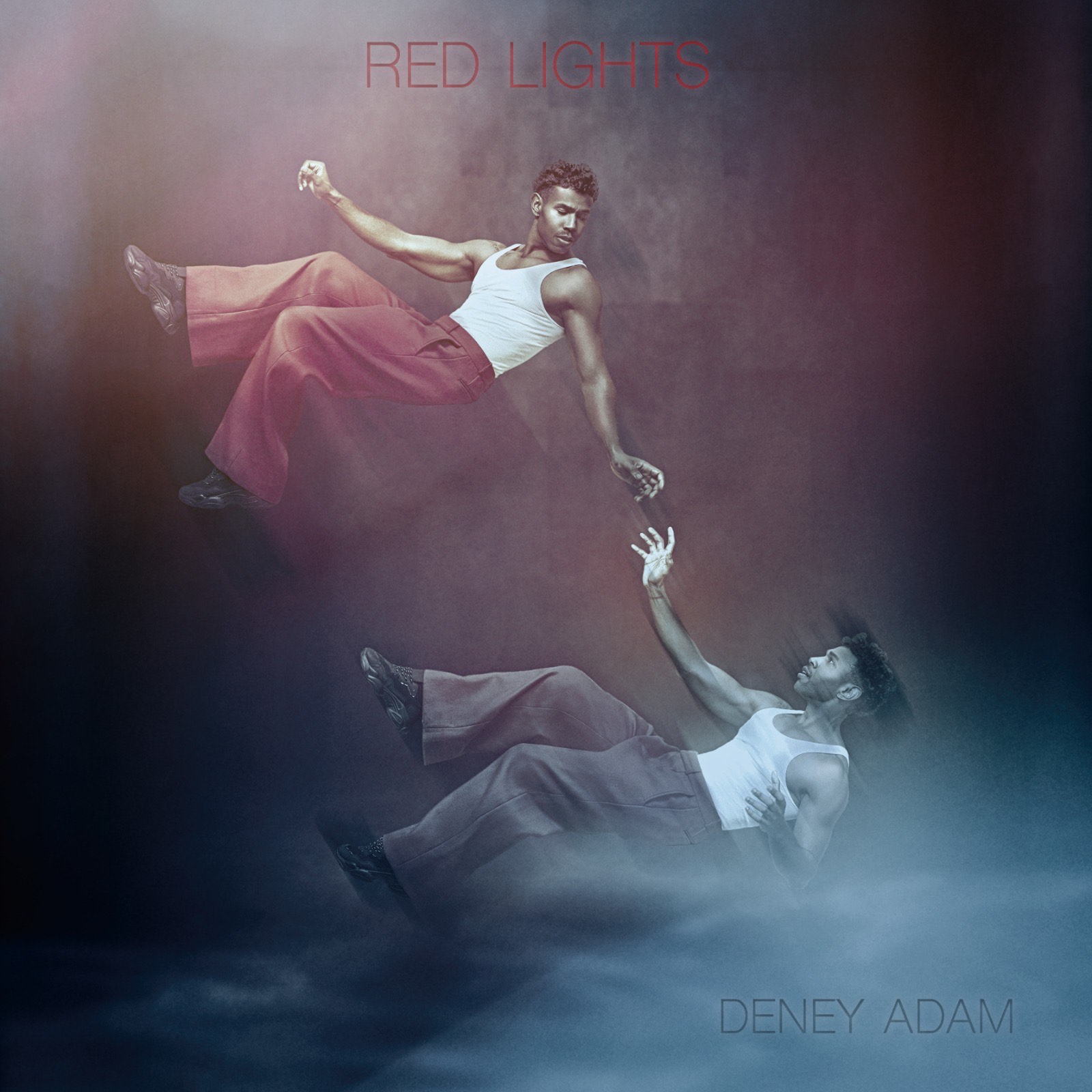

Cover Art // Richard Monsieurs

Deney Adam does not want to be forgotten. He is making music, his lifelong passion, at an almost urgent velocity after years doing celebrity makeup for stars like Lady Gaga and Gigi Hadid. Perhaps years of pent-up emotion are now shouldering through the floodgates in the form of songs. Perhaps he is simply an unstoppably hard worker and creator.

At age nine, he immigrated from his birthplace St. Martin, a small island in the Caribbean, to Long Island, New York. He grew up a Seventh Day Adventist, the worst part of which was not watching TV on Friday nights. The best part, was the singing. He loved gospel music, and as lead singer in the church choir, he cultivated and fed his love for it, like a small bird.

Then, in high school, a glimmer of a path to his dreams appeared. At the time he was about to graduate, at the crossroads of careers and life paths, he got a record deal— but it would soon fall through. They had done some studio time, made some music. But the pop culture milieu was not as accepting as it is now, and he felt the studio did not know how to place him, an openly gay kid. “It was just bizarre,” he tells me. “I was very discouraged. I just wanted to sing, and that happened. So my parents said, you gotta find a job. So I worked at MAC for eight years.”

Even now, at the advent of his music career, he is still doing makeup. “I’ve been a makeup artist all my adult life,” he told me. “I don’t want to give up on makeup because I’m still in love with it.” As for music, his palate evolved from house music to R&B electronic fusion (he laughs in hindsight at how obsessed with house he was). “I’m constantly changing as a person and creative,” he said. “My two biggest fears are to be forgotten, and to not be current. In everything I do, I strive to be current. I guess staying current is a way for me not to be forgotten.”

Like his taste, his process is an ever-changing animal. Right now, his songs begin with a story, a story he would like to tell. A songwriter helps him refine the verbiage and specifics. The vocal arrangements and production are where he truly shines, not only in the singing, of course, but the mapping out of the song, the sketching out of the roadmap of the narrative he tells. Finally, he hammers out the beat, which he makes with producers.

The stories that are the seeds to his songs, are often autobiographical. For his upcoming EP, they are intimately, deeply, heart-wrenchingly so. Some songs are about his ex-boyfriend, who died from an overdose shortly after their breakup. Some, about how Deney himself stopped doing drugs. “Everything is so heavy on this album, because it was a healing process to me, almost like therapy, where I lay it all out on the table,” he said, in an almost heartbreakingly casual tone. “And I felt healed, because my boyfriend— my ex-boyfriend, died from an overdose and I never processed it properly.”

The song “Red Light” was the fruit of this grief. He had dated his ex from 18 to 25, when he passed. “We had a joint phone number together. I still have that number,” said Deney. He had broken up with his ex when, six months later, he killed himself. “I was very guilty. I was very guilty until two years ago. Thinking, if I had stayed, maybe he wouldn’t have die, but you can’t go there. I carried that all the way through life until I wrote this song.” The song and the making of the music video, was a catharsis. “It was a way for me to just be okay. Now I can let him go. And it was so therapeutic. I didn’t know it would be that therapeutic after. I don’t feel heavy. I don’t feel guilty anymore.”

Another song, a dance number, was borne of a different love story. “Blue,” his first Spotify release, was about a man he was madly in love with. Deney was dating another person, actually, when Cupid’s arrow struck. “Oh, I met him, and I was fucking head over heels. I left the person that I was dating, and we were about to move in together,” sighed Deney. “Two weeks after I got this apartment, we were moving in and were gonna be happily ever after. Then he told me, ‘You know what? I don’t think this is a good idea. If you did this to him, you’re gonna do this to me.’” He laughed while reminiscing. “I died! Like, I was depressed for six months. I did not want to get out of bed. I was literally in bed for literally six months.” Yet, in another turn of events, he is now best friends with this former paramour.

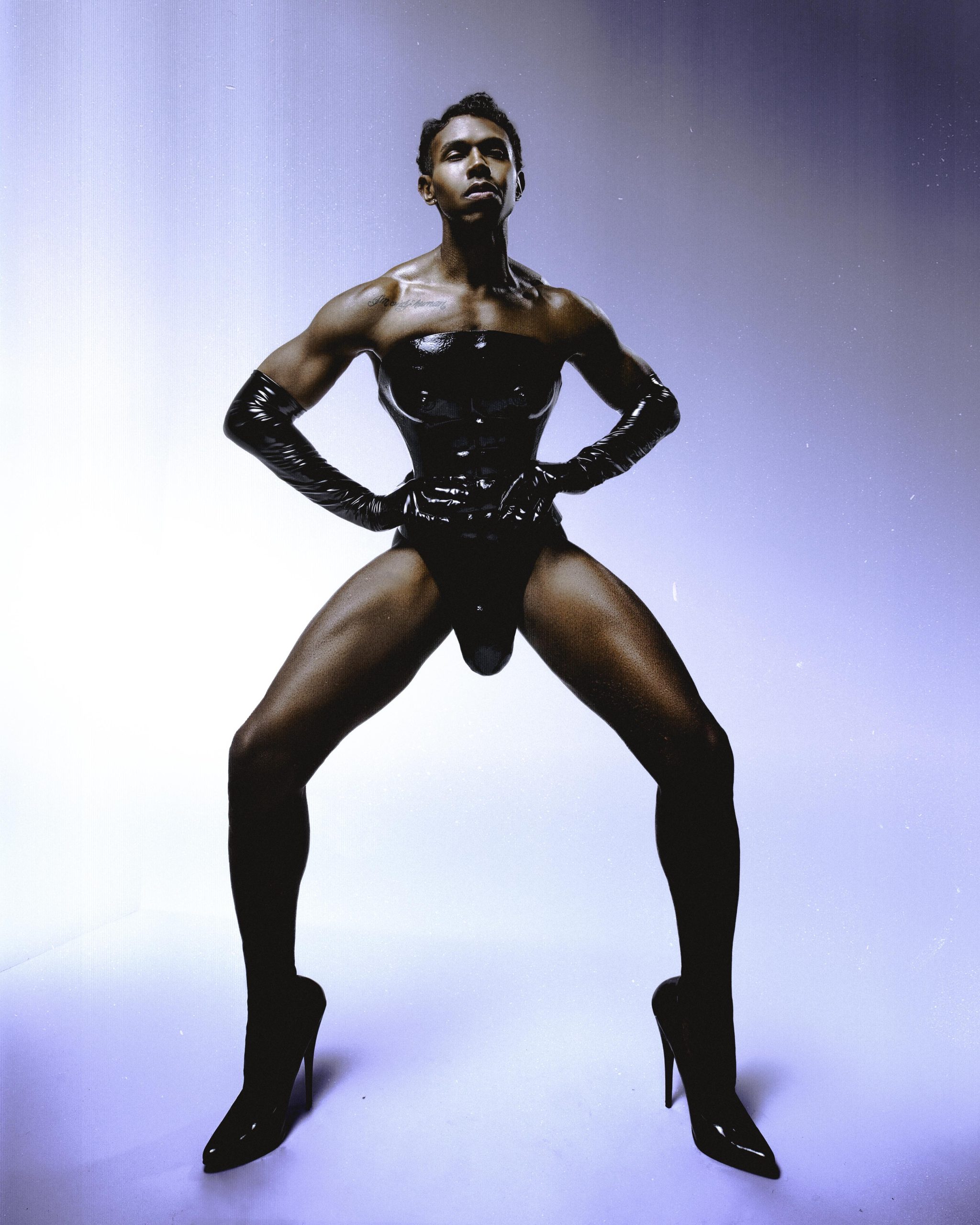

In a group photo with friends at the Mugler Couturissime at Brooklyn Museum, he wears a full body mesh jumpsuit, with a latex fig-leaf design, and latex gloves. He has always been enamored by fashion, and its ability to transcend the mundane, to create a fantasy. “Kudos to artists who want to be real, who want to be relatable. But I could walk down the street and see realism, you know?” he said. “I want to give you something to be irrational about, I want to be an inspiration. I want to give you aspirations.”

In order to last beyond the mortal years we might live, to be unforgettable, it stands to reason that we must first do something immortal, extra-ordinary, perhaps create a fantasy that lives on nothing but everlasting air. Deney is not afraid of death; he just wants to leave a memory behind. He is making that memory, that treasure of Deney-ness for future generations, in his music, that in ten, fifty years someone could disinter on the Spotify of the future. “I want to leave something in this world that people can go back to. I want to leave my mark in this world, whatever that means. I mean, I’m not gonna blow up anything— I mean, in a positive way. Like Marilyn Monroe: 50 years later, we’re still talking about Marilyn Monroe. Elvis Presley, Rosa Parks for that matter,” he said, laughing. “Everything that I’m doing now, I’m doing it intentionally. In the back of my mind, I ask, is this how I want to be remembered?”