From the February 1995 issue of Car and Driver.

Most of my intestinal worms have slithered off to inhabit the GI tracts of pet-shop puppies, so, in retrospect, it’s all vaguely amusing.

But I’d still like to meet the subscriber who suggested this adventure. He had brilliantly breached our militant receptionist’s usually impenetrable screening techniques, blurting, “I’ve got a story so stupid that you better get Phillips on the line, like right now!”

This worked.

“Aren’t you the guy who drove a minivan onto the Arctic pack ice, then fell in?” he asked. Guilty. “Okay, so what you do next is drive a car from Tibet to Nepal. You know, capital to capital. Lhasa to Kathmandu. [Long pause.] You still on the line?”

The man was obviously a fool. I may not be able to find Bucyrus, but my grasp of Asian cartography is unexcelled.

“You seem conveniently to have forgotten a minor topographical anomaly between Tibet and Nepal,” I explained with as much sarcasm as I could drip. “The word Himalayas mean anything to you? Any Union 76 stations recently erected atop Everest?”

“What’s your point?” he asked.

Five Days to Lhasa

And so it was that I expended five days merely flying to Lhasa, getting stuck for 48 hours in Chengdu, China. Chengdu is the capital of Sichuan Province and is a kind of neo-cinderblock Communist version of Akron but with no good Chinese restaurants. The city’s image would improve if all its municipal buildings were fashioned of vinyl-clad double-wides.

I did learn there, however, that the Chinese government is paranoid about untethered Westerners roaming their streets. In true InTourist style, visitors are assigned chaperones. Mine was Jane Chang, who stopped speaking after a semi-ugly discourse that began, “So why are the Chinese in Tibet?”

This turned out to be a good question. In part, they are in Tibet to aim automatic weapons at the sheep who clog the runway at Lhasa’s airport—a facility nowhere near Lhasa, by the way. Or food or water.

For what Tibetans call inji nyempo—or crazy tourists, although these gentle, soft-spoken persons are cursed mercifully by few of those, not counting me—there is one notable drawback. This country, roughly the size of Peru but on approximately the same latitude as New Orleans, possesses an average elevation of 16,500 feet. Try conducting your daily affairs atop Pikes Peak, then add 2400 feet, and you have a grasp of the thing. Or, to make a much clearer analogy, imagine standing at the very top of 82,345 Statues of Liberty stacked end on end.

So I was warned repeatedly to watch for altitude sickness. “How will I know if I have it?” I asked.

“Well, you cough up rust-colored sputum—that’s saliva and blood,” explained the InnerAsia expedition woman. “Then your lips turn blue, you stop urinating and begin vomiting, you get delirious and dizzy and confused and start staggering.”

“I am pretty sure I can recognize that,” I told her. But I simply wrote in my notebook: “Remember New Year’s Day, 1993? That is altitude sickness.”

The cure is to pop thumb-size capsules of Diamox, a mild diuretic, and to wash them down with as much iodine-laced water as you can ingest without Coast Guard Assistance. (All water in Tibet and Nepal, it turns out, is a kind of starter kit for Biology 101 petri-dish cultures.)

Towering over Lhasa is the much-revered Potala Palace, a 1000-room white and brown monstrosity that is the Vatican of Buddhism. Well, it was, until the early Fifties. That’s when the Chinese invaded, encouraging the palace residents—some 4000 monks and their main man, the Dalai Lama—to seek new and exciting countries in which to reside. Today, Chinese workers are drilling three-inch holes in the Potala’s 350-year-old hand-carved timbers so that TV cameras can be installed. Those who know will not say why.

On the streets of Lhasa, human skulls are for sale in a variety of stalls, but locating a rental vehicle in which I could attempt the 590-mile journey southwest to Kathmandu was not so simple. The locals neither speak nor write English, although they are aggressively friendly and are talented at translating wild hand-and-arm gesticulations of inji nyempo. They adore Westerners, a condition that has much to do with Tibet’s having been open to travelers like me for six years only.

I rode around Lhasa in a variety of begged vehicles, including a Yema CQQ1021, a kind of prehistoric Chinese Nissan Pathfinder sans seatbelts and safety glass. Also a Beijing 212, which is an imitation Land Rover Defender 90 with a faux landau top and pop rivets to grip the front fenders. In this particular vehicle’s grille were two rows of jagged teeth cut from discarded truck tires. The idea was to intimidate the immense Dong Feng trucks that carry frowning Chinese soldiers. Plus their guns.

Land Cruiser from Lhasa to Shigatse

After five days, I identified an ’85 Toyota Land Cruiser for rent, this after negotiations to drive a ’94 Suburban 2500SL turbo-diesel—the first GM vehicle ever imported into Tibet—fell to pieces. (In any event, the Suburban wasn’t responding well to the local diesel fuel, which possesses a flashpoint close to that of Miller Lite.)

My beige Land Cruiser cost $1580 to rent. This sounded exorbitant until I learned: (a) The trip would take five days, maybe more; (b) the lone road to Kathmandu, unpaved and often not so much a road as a yak path, would beat the Toyota’s bushings into metallic granola; and (c) the Land Cruiser came equipped with a real, live Tibetan. In this case, 27-year-old Passang.

“Passang what?” I inquired.

“Passang Passang,” he replied. Which is when faithful guide Passang Passang led me to the bushes and whispered my first lesson in being nice to the Chinese.

“Chinese took your travel permit.”

“Took?” I asked.

“Your word, I think, is ‘revoke.’ Not worry. I make new document. Your new name now Doctor P. Jon. So now we go. Give, please, um, $80.”

”What kind of doctor am I?” I asked.

“Surgeon.”

This pleased me, and in response I dramatically waved my Swiss Army knife as if it were a scalpel. Which left Passang as mystified as when I had earlier asked why an immense duck had for the previous day held vigil outside my hotel room door.

Our first day out of Lhasa was our best, logging 219 miles southwest to Shigatse. We might have made it farther, but the Tibetans do not embrace the concept of road signs, preferring instead random stones that hint at kilometer markers.

The morning began with faithful guide Passang explaining that a new Buddhist lama, or Rinpoche, had been installed near Lhasa. An auspicious event, “much good luck,” he asserted. The 10-year-old lama’s title was 17th Reincarnated Karmapa. Here is his other official name: Baiqiadarangqiongwujinjiewaniuguzhuo-duichilieduojiezheqialielangbaerjiewade.

Toward Kathmandu

The 12-foot-wide road from Lhasa to Kathmandu is loosely packed sharp chunks of granite, shale, and chert, alternating with hard-packed sand and the odd glacier or two. The scenery is lifted—sans the Taos T-shirt shops—from New Mexico: brown hills, jagged outcrops, minimal vegetation, and beige dust choking everything that moves. Reposing in the lee of the Himals, Tibet is arid. Add to that dryness a dollop of dizzying altitude and you wind up with a perpetually bloody nose and bone-dry lips. The national food should be ChapStick.

ChapStick would at least taste better. Tibetan food is reviled by even the Tibetans. It consists of slices of meat from yaks that are slaughtered only after they’ve died of old age. Plus yak-butter tea (yak milk and salt), momo (a dumpling with a surprise squid-like chunk of yak at its core), tsampa (blocks of barley held together by yak grease), and chang.

Chang is the local beer. One liter costs about 26 cents. Pour month-old milk into a bottle of flat 7-Up and you will have roughly the same product. Chang’s alcohol content is low, thus imbuing it with no redeeming features whatsoever.

The road from Lhasa to Kathmandu is lonely, littered with an occasional nomad, the odd yak herder, and the random pale-blue Dong Feng truck jammed with soldiers who appear profoundly lost. When we finally did meet an oncoming Land Cruiser, at a pass 17,218 feet skyward, my spirits soared. If parts were required, we could attack and cannibalize. Their Cruiser, newer than ours, courteously backed off the track to within 36 inches of an 1100-foot drop into a mammoth landlocked lake called Yamdrok Tso. The water was the color of Ford’s new fluorescent-purple Probes.

I told photographer Tom Kelly, sitting beside me: “If we go over the side, retrieve my belt. It’s got four crisp hundred-dollar bills inside. Plus my Safeway check-cashing card. You don’t have one.”

The air here was so thin and clear that I was repeatedly tricked by distances. Any mountain whose summit wasn’t cloud-covered appeared climbable. But I noticed that it took two hours just to reach the base of one of them. It is called Nozin Kang Sa, all 23,700 feet of it, a lone, malevolent fang dripping a serrated dagger of a glacier trying to swallow our road. We viewed this at a 16,437-foot pass littered with red, yellow, and blue prayer flags.

“How’d the Buddhists carry flags up here?” I asked Passang.

“Walked,” he said, matter of factly. Then added, ‘Some inji see this mountain, get scared, ask me to turn back.” As if on cue, our right-rear tire simultaneously exhaled 75 percent of its atmosphere.

We lunched in a village called Gyangze. The place could be a Spielberg set, replete with a castle perched atop a 300-foot-tall rock and a 570-year-old monastery surrounded by a mile-long wall 60 feet tall. While photographer Kelly and I searched for ulcer-inducing chang (merely a restorative), Passang patched the tire, then examined the spare and frowned. We crawled beneath the Cruiser to tighten suspension bolts, this after our tame Tibetan said, “I hear them singing.”

In the preceding week, I had perhaps asked Passang 25 times, “What about getting fuel?” He was resolutely silent. But refueling in Tibet’s barren outback was, indeed, unfathomable, principally because anything remotely resembling a gas station refused to present itself—another reason a carry-on Tibetan guide is mandatory.

At one fuel stop, we parked before an adobe hut. Someone’s home. A disembodied hand slipped between dark-blue drapes and proffered a black garden hose.

“How do you know how much to pay?” I asked Passang.

“Don’t know. I discuss how long I hold hose, we work something out.”

Locating our nightly accommodations was another of Passang’s keenly honed talents, but he obviously never flipped through a Michelin Guide. What Passang described as hotels more closely resembled barracks, except that neither running water nor electricity was part of the package. The hotels do offer blankets, a comfort. At 16,000 feet, here, you can predict the nighttime temperature by taking the daytime low and subtracting 38 degrees.

As the days wore on, we lapsed into an uneasy rhythm: shallow breathing, frequent naps, centuries-old monasteries, and brain-hemorrhaging glimpses to the left of the northern scowl of the Himalayas—a white picket fence of horrifying peaks, where there may be sherpas but probably not one who possesses a Toyota shop manual.

During one of my naps, I was jolted awake by an ominous sound: silence. We weren’t crashing over rocks anymore. Passang stood on a ridge, peering intently to the west. looking like a Tibetan Tonto.

Our road had disappeared.

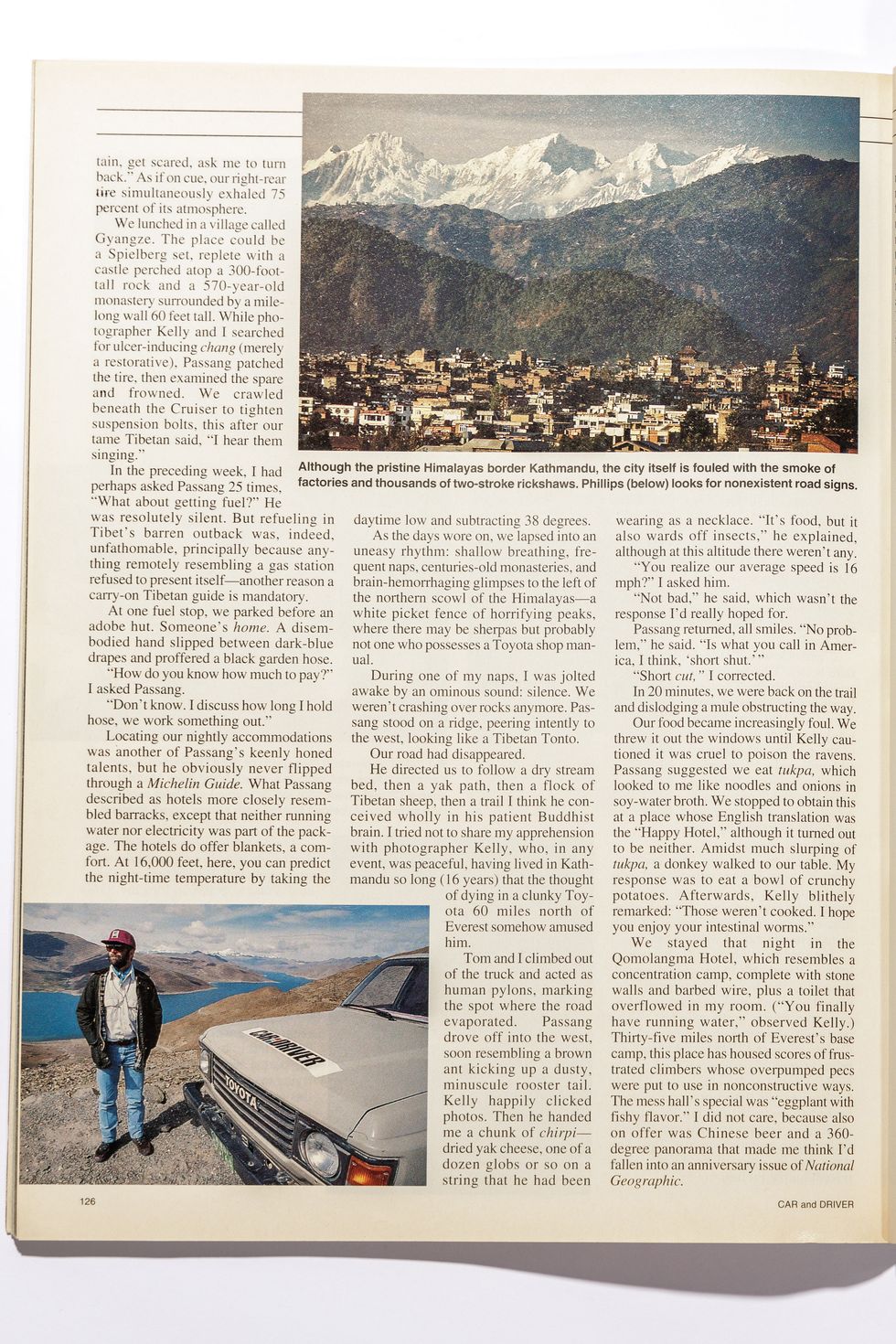

Where the Road Evaporated

He directed us to follow a dry stream bed, then a yak path, then a flock of Tibetan sheep, then a trail I think he conceived wholly in his patient Buddhist brain. I tried not to share my apprehension with photographer Kelly, who, in any event, was peaceful, having lived in Kathmandu so long (16 years) that the thought of dying in a clunky Toyota 60 miles north of Everest somehow amused him.

Tom and I climbed out of the truck and acted as human pylons, marking the spot where the road evaporated. Passang drove off into the west, soon resembling a brown ant kicking up a dusty, minuscule rooster tail. Kelly happily clicked photos. Then he handed me a chunk of chirpi—dried yak cheese, one of a dozen globs or so on a string that he had been wearing as a necklace. “It’s food, but it also wards off insects,” he explained, although at this altitude there weren’t any.

“You realize our average speed is 16 mph?” I asked him.

“Not bad,” he said, which wasn’t the response I’d really hoped for.

Passang returned, all smiles. “No problem,” he said. “Is what you call in America, I think, ‘short shut.'”

“Short cut,” I corrected.

In 20 minutes, we were back on the trail and dislodging a mule obstructing the way. Our food became increasingly foul. We threw it out the windows until Kelly cautioned it was cruel to poison the ravens. Passang suggested we eat tukpa, which looked to me like noodles and onions in soy-water broth. We stopped to obtain this at a place whose English translation was the “Happy Hotel,” although it turned out to be neither. Amidst much slurping of tukpa, a donkey walked to our table. My response was to eat a bowl of crunchy potatoes. Afterwards, Kelly blithely remarked: “Those weren’t cooked. I hope you enjoy your intestinal worms.”

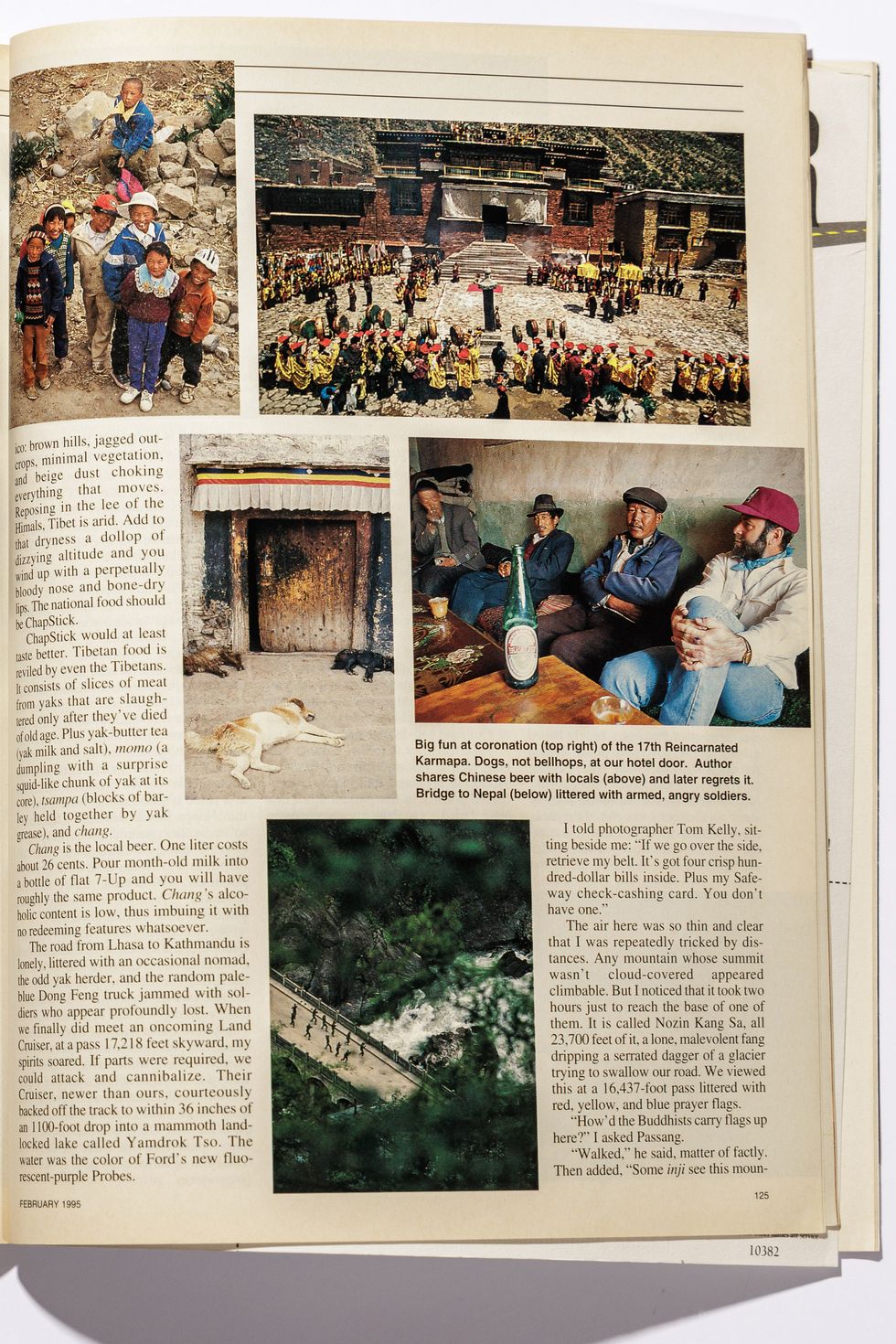

We stayed that night in the Qomolangma Hotel, which resembles a concentration camp, complete with stone walls and barbed wire, plus a toilet that overflowed in my room. (“You finally have running water,” observed Kelly.) Thirty-five miles north of Everest’s base camp, this place has housed scores of frustrated climbers whose overpumped pecs were put to use in nonconstructive ways. The mess hall’s special was “eggplant with fishy flavor.” I did not care, because also on offer was Chinese beer and a 360-degree panorama that made me think I’d fallen into an anniversary issue of National Geographic.

The next day, we made an over-optimistic dash for the Nepalese border, which required not only a climb up the 16,570-foot Lalung La pass but also a potentially ugly run-in with the Chinese at a government checkpoint. I had finally succumbed to altitude sickness, nursing the mother and father of all headaches (the Chinese beer may have been an unindicted co-conspirator in this affliction), but Kelly was a Buddhist bulwark of confidence: “Don’t get out of the car, don’t even look at them,” he instructed.

“They have large weapons,” I noted.

“The worst they can do is deport us, and the nearest country is Nepal, which we’re going to anyhow, and there’s only one road to get there, and we’re on it.”

In this logic I could perceive no flaw. When Passang returned to the truck, he informed me that Kelly’s papers were altered to show he was a Mr. Kahn (a gentleman we’d met back in Lhasa), and that the “Kelly” on one passport and the “Kahn” on the travel permit, never mind the “Doctor P. Jon” on my documents and the “John D. P.” on my passport, had so confused the Chinese that they were unwilling to attempt the requisite bureaucratic disentanglement. Also, it was lunchtime.

A Brief Encounter with Everest

The view of the Himalayas here was, very much in a literal sense, breathtaking, as in, “There is no air”: bristling stegosaurus spines erupting from a beige alluvial plateau, God’s own white-capped exclamation points. Among them were seven of the world’s 10 tallest peaks, this in a country that also possesses an uncharted gorge three times deeper than our own Grand Canyon.

“Let the Chinese drive their cruddy Beijing jeepsters over that,” I said. (We later nearly experienced a head-on collision with one, and Passang demanded that the Chinese back up. They did. Directly into a boulder the size of my house. This pretzeled their tailgate. We continued, smirking.)

To our right loomed a 19,000-foot peak wholly within Tibet, among a snaggletoothed series of massifs, one of them only 3000 feet less statuesque than Everest. In America, it would carry not one but two presidents’ names, such as “Mount Nixon–Slick Willie.” In Tibet, it is nameless, just a good thing to avoid,” noted Passang.

To make up for this lack of names, Mount Everest is also known as Chomolungma, Jolmo Lungma, Qomolangma, and, if you possess some Nepalese blood, Sagarmatha. Observed from the north, it is the pyramid-shaped thing with a lump on its left shoulder. You must climb above the clouds to glimpse its base, as blue as the Caribbean, turning prison-gray halfway up, then Dairy Queen white along the top third. There is an ominous streak up its eastern ridge, as if it has been overrun by a mutant strain of black kudzu.

Whatever its name, Everest, at 29,028 feet, positively resonates with peril, death, and personal disaster. I couldn’t wait to get away from it. At its base was another monastery. The monks there live at the highest permanently inhabited outpost on the planet. They do not move real fast.

Neither did our Land Cruiser, which, at the highest point on our trip—17,120 feet—produced 69 of its original 137 horsepower.

Only 25 miles north of the Nepalese border, we began following a river called the Bhote Kosi, whose foaming whitewater smashed southward at a speed that far exceeded our Land Cruiser’s. This is because, at one point, the gorge loses one mile of altitude in about 50 minutes of driving. The resulting torrent is a hydraulic hacksaw, chiseling between 21,775-foot Phurbi Chyachu on the right and 23,406-foot Gauri Shankar (not the one who plays the sitar) on the left. Because this gorge happens to be a surpassingly rare hole through which clouds can also penetrate the Himalayas, we spent hours fumbling through dense mists that had soaked the landscape so thoroughly that mudslides and avalanches were imminent. In fact, only weeks earlier, a French trekker had looked skyward here during a rainstorm, just in time to see a boulder that was about to crush him so far into the ground that he became a permanent part of the road. Where we encountered old mudslides, Passang instructed that we drive up the gorge face, not down. “More good we rise and fail than fall in river,” he explained. I scribbled this down, certain it was a profound Buddhist aphorism, until Kelly cleared up its significance: “Tibetans cannot swim.” On the other hand, motoring into the woods here also presented the prospect of tigers.

I asked if anyone ever rafted down the Bhote Kosi. “Bad I think for kayaks,” said Passang. “Paddlers all injured, head to rock.”

The next day, we attained the lone filament that connects Tibet to the north and Nepal to the south: a one-lane concrete bridge over the furious Bhote Kosi.

At customs there, the Chinese gaily confiscated my book on the Tibetan Karmapa, then proclaimed that Passang was barred entry to Nepal. Ditto the Land Cruiser, a fate that Passang had predicted a week earlier. And so Kelly and I bade both a fond farewell, and I was overcome by what I later diagnosed as nonspecific surliness.

Across the Friendship Bridge

We hired two porters, aged eight and 10, to carry our cases across Friendship Bridge (a misnomer; the bridge was a parade ground for 40 Chinese Communists practicing bayonet maneuvers), then transferred to another rental Toyota, this one a right-hand-drive miniature. Nepalese driver Dal Khatri asserted it was a “Lettuce,” but the model name turned out to be LiteAce.

The time in Nepal, inexplicably, is two hours and 15 minutes behind the time in Tibet. Which doesn’t really matter, because the year in Nepal is not 1994, but 2051.

From the border to Kathmandu was but a three-hour downhill hump in 90 percent humidity and 90 degree heat, into a city clogged with brick and carpet factories, overloaded buses, thousands of stinking two-stroke rickshaws, 1008 Hindu gods, perpetual outdoor cremations attended by rhesus monkeys (a few of them rabid), and a 70-year-old ascetic named Baba who lives in a cave.

After viewing Baba’s yoga, I muttered, “Holy cow.”

“Actually, here, they are,” Kelly reminded.

He then wandered the alleys of Kathmandu in search of the same medicine veterinarians prescribe for puppies, while I kept practicing—and have now pretty well mastered—the pronunciation of Baiqiadarangqiongwujinjiewaniuguzhuo-duichilieduojiezheqialielangbaerjiewade.