WHEN I FIRST met the Cohutta gobbler, I had no faint suspicion that he and I were embarking on one of the magnificent outdoor adventures of my life.

The time was early spring. The woods were splotched with chalky clumps of dogwood in pastel shades of greens and golds, which made them seem almost unreal. This was spring gobbling season in the mountains, and I was hunting alone in the Cohutta Range, on the Georgia-Tennessee line.

To me, this is one of the most stimulating hunt seasons of the year. The forest floor is bright with flowers, tree buds are bursting with new life, and the vitality of the forest and its creatures seems on the verge of erupting into some unbelievable phantasy of sound and color.

At dawn I’d walked out the backbone of an isolated ridge and paused to listen for the sonorous notes which would indicate a big buck turkey on the prowl. For an hour I stood there with my back against an oak tree, while the dawn woods came to life and the sun touched a distant mountain with burnished copper. I yelped the cedar box in my hand. When the call went unanswered, I strolled another quarter of a mile to yelp the box again and listen for a reply.

That was when I first heard him, somewhere beyond the wildest jumble of ridges and valleys imaginable. His notes were resonant with volume, denoting a large gobbler.

The closer I could get to that gobbler without spooking him the better would be my chance of putting him in the bag. So I struck out in a beeline, across the ragged series of ridges, navigating the rough valleys and pausing on each ridge to call again and get an answer.

On the fourth ridge, I sensed that he was somewhere near. When I clucked my yelper and didn’t get an answer, I considered that the bird and I were at close range. So I stood still, straining my ears, and after a few minutes heard some creature working in the dry leaves which blanketed the shallow cove just beyond the hilltop. The crest of the summit was thinly clad in laurel, and the ground around the thickets reasonably bare of leaves. In a half crouch, to keep my head below the narrow backbone of earth, I circled to a point directly above where I heard the parched leaves rattling.

After listening for a minute, I concluded that the sound was definitely that of turkeys scratching for sustenance in the brown carpet, though they hadn’t made a note of any kind to verify their presence.

I stood perfectly still, trying to determine what my next move should be.

I’m reasonably sure I’d have concocted some scheme to get a look at those birds, if a gray squirrel hadn’t taken that exact moment to travel through the scrubby timber. When I heard the squirrel rattle bark on a tree above me, I instinctively glanced up. He was so close over my head that I could have touched him with my gun barrel. I had on my camouflage suit, but my face was uncovered. When he identified me, the bushytail seemed to go berserk.

He made a long leap to the next tree, another flying arc, and on his third jump he either misjudged or broke a limb in his headlong flight. I got a glimpse of him in the air and then heard him hit the leaves on the slope below.

If those startled turkeys had taken to the air, I could have killed one. They were scratching within 40 feet of where I stood. When I heard them running in the leaves, I charged into the laurel, hoping for a shot, but by the time I spotted them, they were sprinting up the far slope, out of shotgun range. One was the tallest gobbler I’d ever seen in the woods. A couple of young bucks were with him, and the old tom simply dwarfed them.

The season was running out, but I put in my last eight days on the trail of that big buck turkey. I know I climbed 100 miles high, adding all those slopes together. Joel Biggs, local wildlife officer, told me that turkeys often range as far as four or five miles, and I must have looked in every cove and on top of every ridge in a large portion of that 20 square miles. I hunted through the open seasons in Georgia and Tennessee and on the Ocoee Wildlife Management Area. On five different occasions I could have put a young gobbler in the bag, but each one I passed up. One had a raspy voice that I was sure belonged to my old bird, but when he walked around the end of a log, 50 feet away, I saw that his beard was no longer than my index finger.

I was stricken with big-turkey fever. The big gobbler had my tag on him, and I wanted him more than any trophy I’d ever brought home.

I met one other mountaineer who was on the trail of this same bird. Gobbler hunters have a special feeling of camaraderie. If you happen to meet on a high ridge or an isolated woodland trail, it’s like two Daniel Boones bumping into one another. You exchange cordialities either by sign or in whispers, briefly swap plans so you won’t conflict with the other hunter in choice of territory, trade bits of information on fresh scratchings or other sign you’ve seen. You might even take a few minutes to compare the tones of your cedar box or other call. Then for the remainder of the day you listen for the sound of the other man’s gun, hoping all the while you won’t hear it.

This grizzled mountaineer had come down the trail as softly as a forest cat to where I sat with my back against a tree. After the usual ritual of exchanged greetings, he showed me his call and I clucked my own for him. The old fellow listened with a slightly cocked ear to the notes of my box, then nodded.

“These gobblers around here sure oughter like that Southern accent,” he said.

During my hunt for the long-bearded one I learned all over again that to kill a large wild gobbler is perhaps the greatest challenge in hunting. It doesn’t take the courage needed to coldly face a charging grizzly or the stamina necessary to climb for a mountain goat or trophy ram. But nothing requires more in woodsmanship, patience, and know-how than gobbler hunting.

ON ONLY ONE other occasion that spring did I figure I was close to the grandpa gobbler. It must have been a couple of miles from where I’d first seen him. He was on the Georgia side, in the last day of the Georgia open season. I was traveling a long “lead” (local word for a main ridge) just after daylight. When I paused on the brow of a slope to call, he answered. At least I thought I recognized his voice. I made a breathless detour of more than a mile to the ridge above him, but before I could get into position half a dozen crows spotted the tom. From their language, they were really working him over.

I crept downhill as close as I dared get to the melee and set up my business. For more than an hour we maneuvered around on that point of ridge. Finally the crows, or something I said with my cedar box, spooked him. The gobbler turned away, crossed a shallow cove to the thick laurel on the next ridge. He was traveling too fast for me to even try to get above him. But where he’d paused to scratch in the soft earth I found his tracks, and they were enormous. I’m sure it was the big bird.

During the winter I learned that this gobbler had quite a reputation in both the Cohutta Mountains and around Ocoee. Several of the local sportsmen had an eye on him, and one or two had devoted most of their spring gunning hours to the bird. So I approached another April season with the growing apprehension that one of those mountain men might get to the gobbler before I had another chance at him.

This foreboding grew acute when I had to miss the first three days of open season. My only consolation was that spring came later than usual, and those first legal days were rainy and cold, which might somewhat dampen the ardor between toms and hens, normally in full blossom at this time of year.

On the morning of the fourth day I was in the woods half an hour before daylight. The brown carpet of leaves was white with frost and a cold blanket of air lay across the hills.

In the woods with me this time were my wife Kayte and Phil Stone, a Dalton, Georgia, businessman who’s one of my regular hunting partners. Since turkey hunting isn’t one of the things three people can do better than one fellow by himself, Phil Stone decided to hunt alone down a dim logging road that skirted the narrow valley. Kayte stayed with me.

AS THE FIRST dawn light turned the woods from black to gray, a ruffed grouse flashed across the road in front of us. Farther down the valley, we flushed two more of the colorful birds out of a branch bottom. The dawn was bright and cold when we climbed the point of a long ridge overlooking the valley. From this spot we were close enough to hear if a turkey called from any of half a dozen ridges sloping away from that massive range around Big Frog. We got settled and waited until the noise we’d made on the frozen leaves was forgotten by the forest creatures around us and they began to move again.

On my box, I gave the low, plaintive notes of a hen. After a few minutes with no answer, I called much louder. A quarter of an hour later, I rattled the box with the throaty call of a gobbler. All this activity produced exactly no results, except the raucous notes of a crow across the valley and the loud drumming of a woodpecker on a hollow stub.

Kayte and I climbed over the crest of the ridge into the next valley and repeated our performance. The sun spotlighted the tops of the highest hills around us and the line of sunlight crept down the mountains until it touched and warmed our half-numbed hands and cheeks.

We moved from one ridge to another, but heard nothing that sounded like a turkey. At 8:30 a.m. we made our way back over the trail to where we met Phil Stone, who’d also gone through an unproductive morning.

We discussed the situation and decided that, with the retarded season, the birds were not yet talking. I felt a sense of relief, rather than disappointment, since I now had the impression that my big gobbler was safe and that I might see him again.

“Just so we can say we gave this hunt a last-gasp effort,” I suggested, “let’s try one more call before we go back to the cabin.”

I walked out to the edge of the road, clucked a couple of times, gave the low wailing notes of a hen, and listened. Merely to complete the routine, I rattled my box. It was answered immediately from the next ridge by the sonorous roll of a gobbler. Phil and I stared at each other, as though we sought confirmation that our ears were not playing tricks.

“Stand here a few minutes,” I whispered, “and let’s see which direction he’s headed.”

When the buck turkey gobbled again, he was 100 yards farther down the ridge. That was enough for me. My two partners agreed that I could travel faster and get in ahead of the gobbler if I went alone, and that I might have a better chance of seeing him, to determine if he was the bird we wanted.

I climbed the slope on a half run. At the spot where I hoped to intercept the gobbler, I zipped up my camouflage suit and sat down at the base of a big tree with emerald vegetation growing in front of it.

I wasn’t sure whether it was my call the tom answered, but he gobbled again shortly after I’d given him the soft, gentle notes of a hen on my slate-type call. Minutes later, a second gobbler with a younger voice made the woods ring off to my left.

The smaller tom definitely was coming to me, but the larger turkey walked off the ridge he was on, crossed the branch in the hollow, and climbed to a cove that angled away from where I’d taken my stand.

The sunlight on his feathers made them ripple in a display of copper, green, and gold so resplendent that I caught my breath at the spectacle.

I left the young buck turkey decoying to my squeal and took off down the slope after the gobbler we’d first heard. I tried to convince myself that I hadn’t acted foolishly in giving up a bird in the hand for a try at the old boy with the rusty pipes. But the big tom had already cost me five smaller gobblers, birds passed up the spring before, and I figured he should be worth at least one more.

By midmorning the leaves had lost their dawn coating of frost and most of the moisture from the resultant saturation. The drying forest floor was much noisier underfoot. I had to pause every few minutes to get another fix on the gobbler. We were walking at about the same speed, and by the time I reached the road which separated Georgia’s Cohutta Range from Tennessee’s Ocoee, the tom had crossed the road and climbed the side of a massive mountain in the forbidden area.

It looked like the end of the trail for that day. The Ocoee area was closed except for five two-day periods in April, and I wouldn’t have another chance at him until then.

I DIDN’T BELIEVE I was capable of enticing the bearded old patriarch back down the mountain, especially when he seemed so intent on going the other way since the moment we first heard him.

But I had nothing to lose by trying. I whacked my cedar box with a couple of lusty yelps, and he came back instantly with a deep-throated gobble. I settled down in a little clump of pines to wait. It was at least 10 minutes before his resonant voice rolled down the mountain, and again he seemed farther away than he had been. The next time he clattered, he was near the top of the mountain, and going away. So I gobbled the box as loud as I could make it quaver.

For 20 minutes there was complete silence. Then he sounded off again, from approximately the same spot where I’d last heard him. My heart gave an extra thump, because I’d at least stopped him temporarily.

I waited and waited and waited. have no idea how long I sat in that one spot, trying to make up my mind that he’d gone on over the mountain. I suppose the only thing that kept me glued to the seat of my pants was the knowledge that many times when a tom stops gobbling, but hasn’t been spooked, he’s coming to investigate. If so, there wasn’t any harm in giving him my exact location. I reached stealthily for the slate and cedar stick, touched it softly for a few dainty clucks, then dropped it beside me on the ground.

To wait and keep on waiting requires an enormous amount of patience, when there’s no hint of any kind whether you’re on the verge of success or failure.

AT LAST I HEARD a stick crack somewhere, and then a rustle of leaves. I thought it might be a deer, and without turning my head, searched every inch of the forest for movement. I even considered the possibility of another hunter stalking me.

Another small twig snapped, and I had my eyes on the exact spot when the turkey’s head came in sight. All I could see was the meaty, wrinkled part above his wattles. There was no way to tell whether he was the old gentleman with the long beard. He wasn’t coming directly to me, but at an angle, as though he expected to completely circle that clump where he’d heard the last wavering note of a hen. He wasn’t more than 20 yards away.

He took two steps and I could see more of his head, but not the beard, or judge his size. He put down his head to peck at something on the forest floor. I raised my gun quickly. On its way up, the gun dislodged a dead Y-shape twig that straddled and hung on the barrel in such a manner that I couldn’t see the sights. The bird continued to walk, growing taller under the shoulder of the hill, and I moved the barrel slowly to keep it in line with his head.

It was purely a matter of luck that at the time my gobbler walked behind a tree, a growing twig in the close quarters flipped the Y-stem from my gun barrel. When the tom stepped around the tree, the sights were on his head.

My 12 gauge Winchester pump gun was loaded with cartridges holding No. 6 shot. Some turkey hunters like larger shot, No. 2’s, say, but I think I have a better chance of hitting the vital parts of the bird’s head and neck with the dense pattern of No. 6. Most shots in this type of hunting are at the bird’s head and neck while he’s on the ground. I often back up the first load of No. 6 with a No. 4 and then a No. 2 load, which gives me reserve loads of progressively larger pellets to break down a turkey that flies or runs after the first shot.

In a patch of sunlight he stood for five seconds with his head up, as huge as I remembered him from the spring before.

In a patch of sunlight he stood for five seconds with his head up, as huge as I remembered him from the spring before. He was so close it seemed that I could reach out and touch him with my gun. The sunlight on his feathers made them ripple in a display of copper, green, and gold so resplendent that I caught my breath at the spectacle. Then I saw his long, heavy beard, and knew beyond doubt that he was the old patriarch I had dreamed about all winter.

It was almost sacrilegious to shatter that magnificent moment with a shot, but the powerful impulses developed in a lifetime of hunting triggered the gun. It was a clean, one-shot kill.

Then all the excitement of the past two hours hit me, and my hands shook as I tried to unstrap the camera from my shoulder. When I hefted the bird for weight, and saw how far I had to lift his feet so that his head would clear the ground, I got the shakes again.

He pulled the hand on the corroded old camp scales to 25½ pounds, the largest mountain gobbler I’ve seen, and one of the biggest turkeys I’ve ever killed, including the larger breed from the Southern plantations. Phil looked over his glasses at the scales.

“There just ain’t no tellin’,” he said, “what this critter would have weighed if those scales weren’t so rusty.”

At the moment, the gobbler’s actual weight didn’t make too much difference. He had given me my finest hour in the turkey woods.

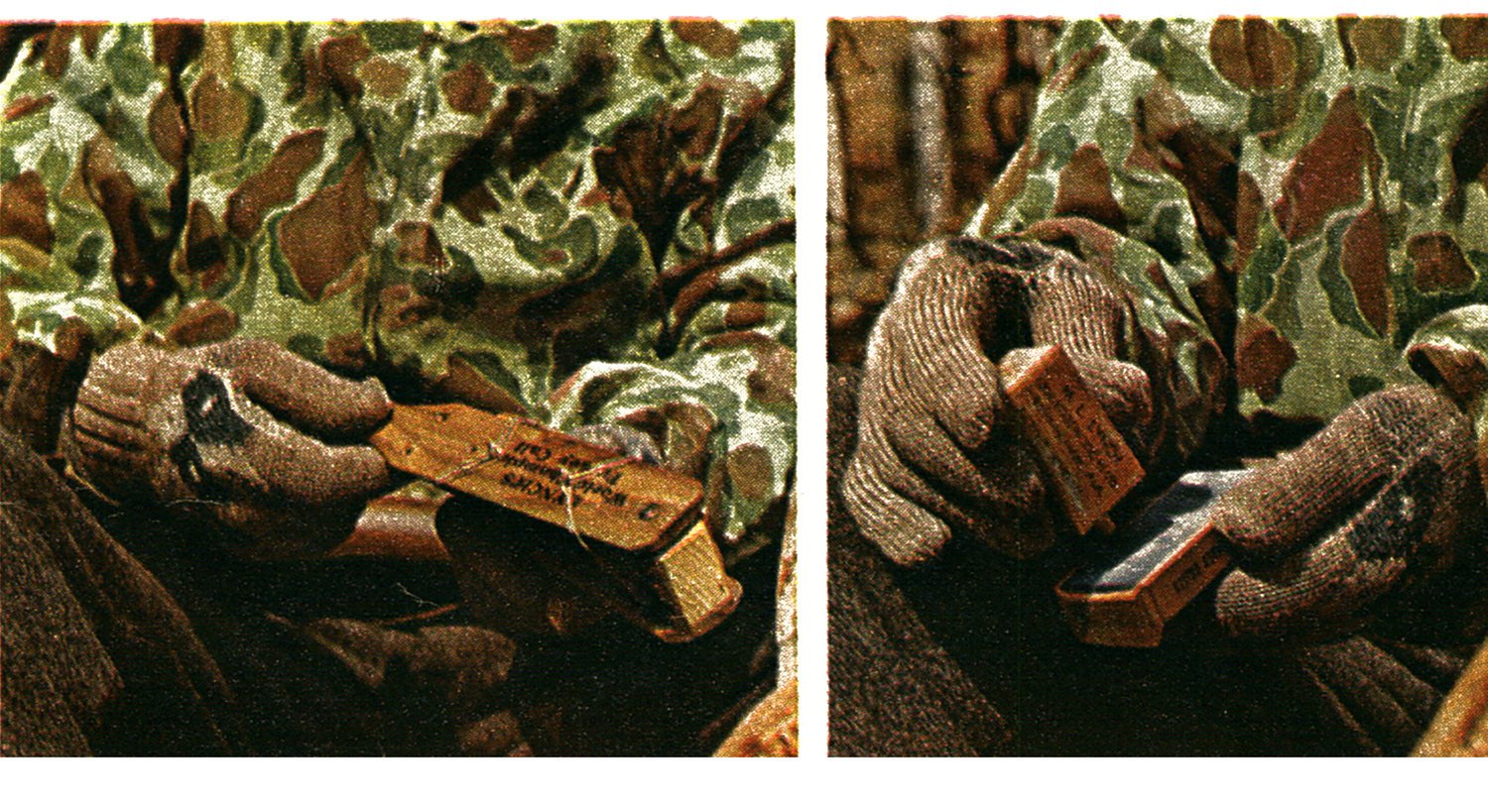

TURKEY CALLS

Of all the commercial and homemade devices used to call turkeys, the author has most faith in the two shown here. First is the box type-a hollow box made of cedar. The lid of the box has a pivot screw at one end. Calls are made by scraping the cedar lid across the top of one side or the other of the box. Chalk or rosin improves tone. When turkey is close, Elliott switches to second caller-a thin piece of slate that he rubs with pencil-thick nub of charred cedar protruding from cedar block. Friction between charred cedar and slate produces call of hen turkey.

This story, A Bearded Legend, originally ran in the March 1962 issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.