A new survey of Americans’ attitudes toward hunting, fishing, trapping, and recreational shooting shows support for all those activities dropped over the past three years, even as the Covid-19 pandemic pushed more people into America’s woods, waters, and shooting ranges.

The drop in public support for legal field sports comes after nearly 30 years of increasingly favorable attitudes, and may reflect a wider and growing discomfort with activities that are considered the domains of mainly white, rural, older males.

The “Americans’ Attitudes Toward Legal, Regulated Fishing, Target/Sport Shooting, Hunting, and Trapping” survey, conducted by Responsive Management, was released last month by the Outdoor Stewards of Conservation Foundation, a think tank devoted to communicating trends in outdoor activities.

The multi-modal survey of over 2,000 respondents was conducted this spring, and asked participants from every region of the country a wide range of questions about their attitudes toward regulated hunting and fishing, recreational shooting, and regulated trapping. Public approval for each activity showed declines from a similar survey conducted in 2019. In some cases, it recorded the lowest approval rating for some types of hunting in 30 years of similar surveys.

Public approval of legal hunting dropped 4 percentage points over the past two years, from about 81 percent of Americans in 2021 to 77 percent of Americans this year. Approval of recreational shooting dropped 3 percentage points, and approval of recreational fishing also dropped 3 points, to 90 percent favorability.

Respondents were not only asked if they strongly or moderately approve of those activities, but also if they strongly or moderately disapprove of them. That disapproval rating was also among the highest recorded in the decades-long survey. Seventeen percent of Americans strongly or moderately disapprove of legal hunting, 18 disapprove of recreational shooting, and 5 percent disapprove of fishing.

Public attitudes toward trapping are perennially low, with about 54 percent of Americans approving of regulated trapping and 28 percent expressing disapproval with the activity.

The survey drilled into public attitudes about methods and motivations for hunting, and again, nearly every category saw statistically significant declines over the past few years. Hunting either to protect humans from harm or for wildlife management purposes had the highest approval rating, at 78 and 77 percent, respectively. Hunting “for the meat” had a 75 percent approval rating this year, down from 84 percent in 2019. Surprisingly, hunting “to get locally sourced food” or “to get organic meat” showed major declines in approval, down 11 and 14 percentage points, respectively, from a similar question in 2019.

Deer and wild turkey hunting had the highest species-specific approval ratings, with 70 percent of Americans approving of deer hunting and 69 percent of Americans approving of turkey hunting. Hunting for rabbits, ducks, squirrels, elk, and alligator all had approval ratings of over 55 percent. But when asked about legal hunting for black bear, dove, grizzly bear, wolf, and mountain lion, public disapproval exceeded approval.

Some 69 percent of Americans approve of hunting with a bow and arrow while 66 percent approve of hunting with a firearm. Fifty-two percent approve of hunting with dogs. But disapproval exceeded approval for methods of hunting that imply that humans have too much advantage over wildlife, including using scents that attract game, hunting over bait, hunting on a property that has a high fence around it, or using high-tech gear for hunting.

Results of this most recent survey are worth considering, says Mark Damian Duda, executive director of Responsive Management, which conducted the survey. Duda has been surveying Americans about their attitudes toward hunting, fishing, trapping, and shooting for over 30 years, asking generally the same questions every three years or so in order to establish reliable long-term trends.

“This survey is quite sensitive to changes in attitude, and all of the drops in approval are statistically significant,” says Duda. “These are not incremental changes, but rather meaningful drops. Each one percent of change represents 2.5 million Americans, so when we see approval go down by 3 to 4 percentage points, we’re talking about as many as 10 million Americans.

“Two years ago—when we last conducted the survey—we had 81 percent support or approval of legal hunting,” he adds. “Now we have 77 percent. And on the other end of the spectrum, when we ask about disapproval of hunting, we see that rise from 12 percent to 17 percent of Americans. That’s worth looking at and taking note of.”

Duda cautions people not to dismiss the survey as a single point in time.

“Yes, this is a single study we’re talking about,” he says. “But I saw indications of these trends at the very beginning of the year. Our company does a lot of individual state surveys every year, commissioned by state natural-resource agencies, and I saw the decline [enumerated in the national survey] in five different states and five different studies. When you see the same results in conglomerate, then you can have strong confidence in the trend, and that it’s not an expression of a single point in time or point of view.”

Hunting Approval Depends on Region and Demographics

While 77 percent of Americans strongly or moderately approve of legal hunting, only 65 percent of African American residents approve of legal hunting. The group with the lowest approval of legal hunting—at 61 percent—is Hispanic or Latino Americans. And in terms of age groups, while 81 percent of Americans age 55 or older approve of hunting, only 69 percent of respondents from 18 to 34 years old approve.

Generally speaking, the groups that had the highest favorability toward hunting are those who have hunted, shot recreationally, or fished in the past three years, live in a rural area, are male, white or Caucasian, 35 years or older, live in the Midwest, and reside in a small city or town.

The groups with the lowest approval of hunting are Black, Hispanic, did not fish or shoot in the past three years, are between 18 and 34 years old, are female, live in the Pacific West region, and reside in a large city, urban area, or suburban area.

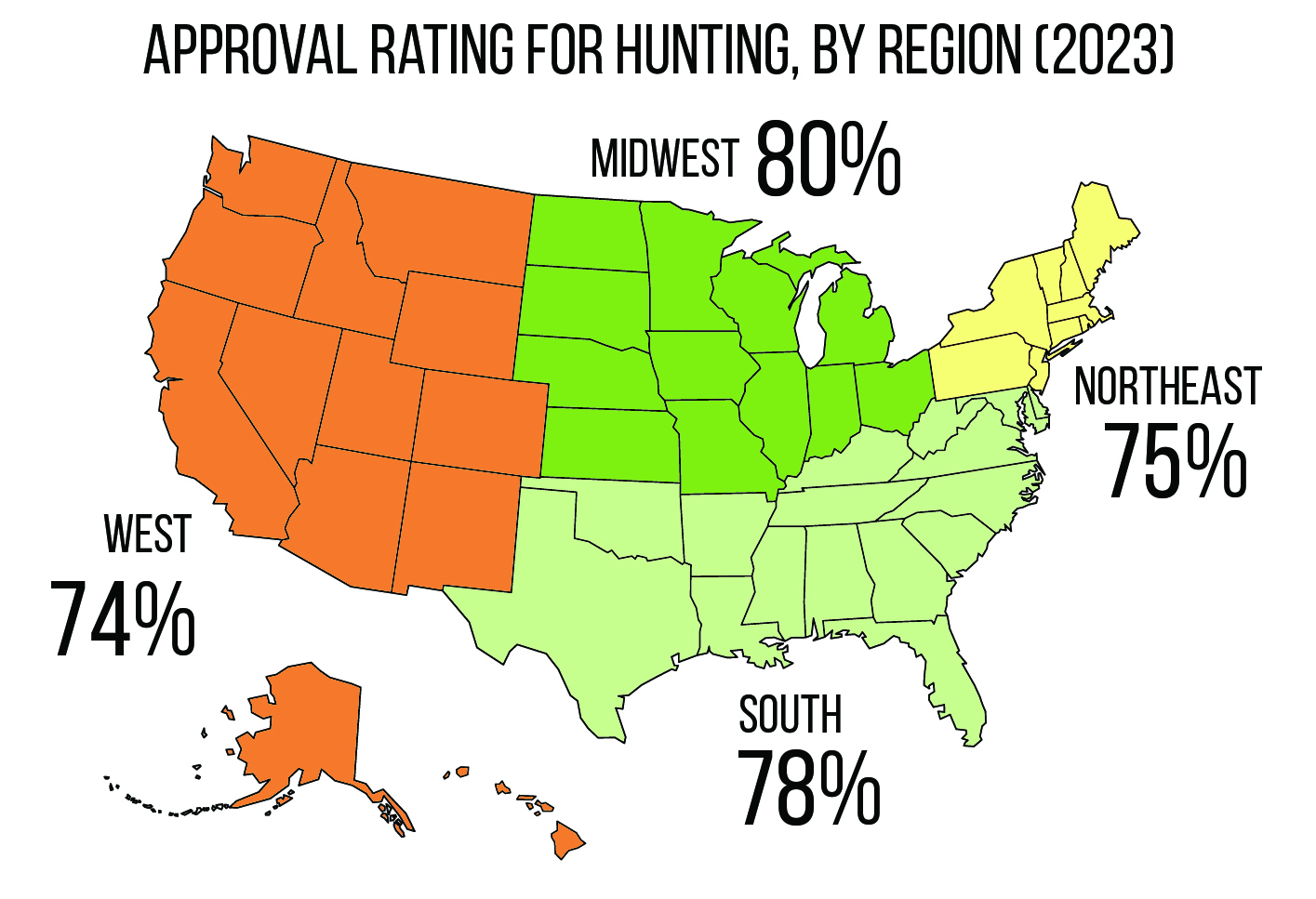

Regionally, the lowest approval rating for hunting was in the West, where 74 percent of respondents said they strongly or moderately approve of hunting. The approval percentage was 75 percent in the Northeast, 78 percent in the South, and 80 percent in the Midwest. The region with the highest disapproval rate for hunting was the West, with 20 percent disapproving of the activity. Only 13 percent of Midwesterners reported disapproving of hunting.

The survey also measured regional attitudes toward recreational shooting, legal recreational fishing, and regulated trapping. The region with the highest fishing approval was the Midwest (92 percent) followed closely by the South (91) and the West (90 percent). Approval for recreational shooting was strongest in the Midwest, with 82 percent favorability. Meanwhile, only 73 percent of New Englanders approve of shooting, with 22 percent disapproving of the activity.

Support for trapping was strongest in the Midwest, with 54 percent approving of the activity. It was lowest in the West, with 51 percent approving, and 32 percent disapproving.

Is it Okay for Other People to Hunt?

For more than two decades, respondents to the survey have been asked whether they agreed that others can hunt in accordance with regulations. The idea for the question is to get a feeling for indirect support, even if respondents themselves don’t hunt.

This year, 86 percent of respondents strongly or moderately agreed that it’s okay for other people to hunt. That’s a significant decline from 2011 and 2019, when 95 percent and 92 percent, respectively, of Americans said it’s okay for other people to hunt. It’s a question that may have implications for ballot initiatives or other electoral attempts to regulate hunting or wildlife management.

The groups most likely to strongly or moderately agree that it’s okay for other people to hunt are, not surprisingly, similar to those who support hunting in general: those who have hunted, fished, or shot in the past three years, live in rural areas, and are Midwestern white males over 34 years old.

The groups least likely to agree that it’s okay for other people to hunt: Hispanics, Blacks, Americans from 18 to 34 years old, and urban females from the West Coast.

Duda says this particular question is among the most resonant of the survey, because it gets at hardening opinions about hunting and shooting.

“I’m a researcher, and it’s not my business to tell you why we’re seeing these changes,” Duda says. “But I can tell you that we are definitely losing support among younger Americans. We [sportsmen and women] are not talking to Black or Hispanic communities, and we need to do a better job of reaching urban people and women.

“In my opinion, our community has a lot of work to do,” continues Duda. “We need to put more money and effort into campaigns to increase the cultural support for hunting. There are some good efforts out there—the National Wild Turkey Federation has been a leader, and I wrote a book called How to Talk About Hunting that gives some concrete suggestions of what needs to be done. Some of it is obvious. If you’re posting on Facebook and talking about ‘killing-and-grilling,’ you are not helping the cause. When we talk about hunting and shooting, the words we use are incredibly important, and the way we portray what and why we do matters.”

Duda also thinks larger cultural divisions are influencing Americans’ attitudes toward hunting, shooting, and fishing.

“In the past, people might be okay with other people doing all these things, but now that people are increasingly picking sides, I think there’s a perception that if people belonging to another group do these things, then they automatically oppose it. And of course, that’s accelerated when people don’t have personal, positive experience with these traditional activities of hunting, fishing, trapping, and shooting. I think we need to actively introduce or reintroduce these activities to more new people.”