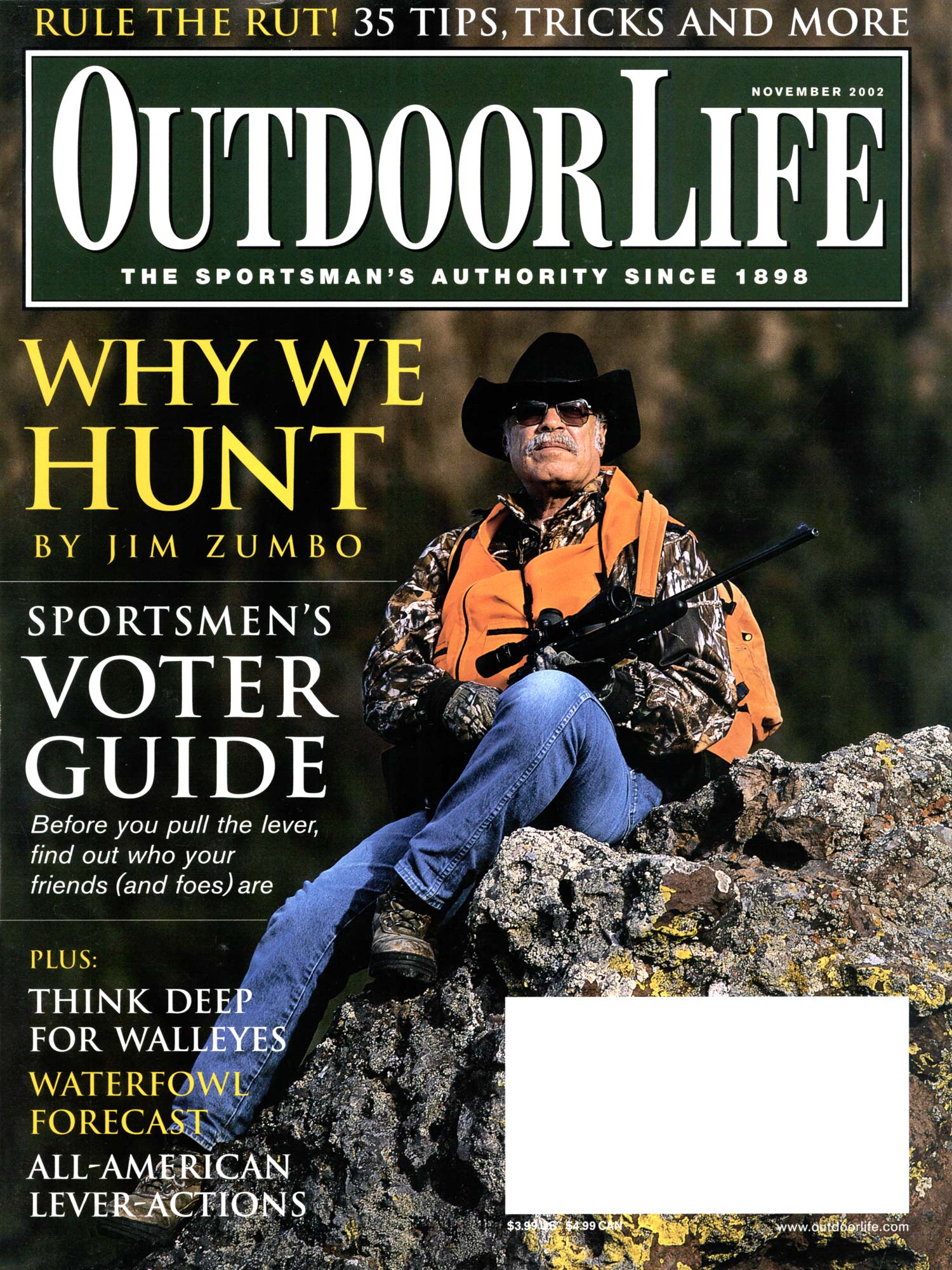

This story originally appeared in the November 2002 issue.

IT HAPPENS almost every year. I sit on a ridgetop in September, hunting elk somewhere in the Rockies. Flocks of geese fly high overhead in V formation, headed south to their wintering grounds. The honking seems to touch my very soul, and I’m not embarrassed when my eyes begin to tear, even if I’m with someone. But my mood inexplicably changes as I fast-forward to an anticipated day in November when I’ll be lying among decoys, trying my best to shoot a limit of geese out of the sky.

That I can experience two such diametrically opposed emotions in practically the same moment is, I believe, the biggest enigma in hunting. How can we love and admire a wild animal one minute and look forward to taking its life the next? I cannot completely answer that question, although I’ve heard it discussed many, many times. I’ve never heard or read a succinct explanation, and I don’t believe it can be explained in simple terms, though several philosophers have tried. It’s far too complex an issue.

We hunt for many reasons. Early on I learned that outings with my dad, grandfather, uncles and cousins resulted in a delicious rabbit and squirrel feast. Fifty years later, I still love the taste of the wild game I bring home—any kind of game. To be sure, the consumptive aspect of hunting, that of bringing the quarry to the table, is one of the primary reasons I hunt. Take the musk ox I hunted recently in late summer. I opted to drive as far north as I could so I’d have fewer flights and would maximize the time that the meat would travel safely with me in my pickup truck en route to my freezer. One of my biggest fantasies was fulfilled when I shot my first bighorn sheep and cooked the ribs over a campfire to see if Jack O’Connor was right when he said sheep was the best wild meat he’d ever eaten. My concerns over hunting in Africa were dispelled when I learned firsthand that every ounce of the quarry is utilized.

Since I’m intensely focused on the culinary aspects of the animals I hunt, I have no problem shooting a forked-horn deer or a spike bull elk, and I won’t apologize for it. That’s not to say I won’t hold out for a so-called trophy if I’m hunting in a trophy area and think I have a pretty good chance of getting one. I believe I speak for most of us when I say that a 10-point whitetail is a lofty objective but a lesser buck will do. And if that’s not possible, a doe may suffice. Not many of us are pure “trophy hunters.” I know a few. Most of them go on high-dollar hunts where the antler score means everything. The rest of us are mainly interested in simply bringing home any legal deer, elk or whatever species we’re hunting. My job as a hunting writer often pressures me to tag the biggest animal I can find. That’s really not me, but I do feel a sense of it being my duty. That’s why I’m most happy when I can literally walk out the front door of my home, hike up the mountain and shoot a cow elk—no cameras, no obligations, no expectations, just me and the mountain and the elk.

The Challenge

I love the many challenges of the hunt. I live in Wyoming, and two years ago I drew a tag to hunt bighorn sheep in my home state. I had several invitations from outfitter pals to hunt with them but I wanted to hunt my ram on foot and alone. To me, the exploration of new country, walking ridges I’d never walked before, working my way up over avalanche chutes and steep canyons, was an exciting mini-adventure. I remember standing on a lofty peak after a grueling 10-mile hike and looking across the most incredible mountain scenery in the Rockies. I sat for a long, long time and soaked up the view. I knew I could never explain my feelings about what I saw and felt.

Last year I drew a Utah moose tag. I turned down offers of assistance and hunted the moose solo. I’ll never forget that hunt, or the pain and frustration of single-handedly transporting my moose, piece by piece, to my pickup truck. There’s a tremendous sense of accomplishment when you overcome adversity and do it your way. That, in itself, is one of the reasons I hunt.

The mental challenge and physical skills needed to hunt well turn me on, too. Calling in a bull elk or rattling up a whitetail buck with no help from anyone is exhilarating. The whole process of setting up, making the correct sounds, receiving and interpreting the response from the quarry and reacting correctly to make a clean kill is what it’s all about.

I also love the competitive challenge. I like hunts where heavy pressure requires me to hunt smart, whether I’m after a whitetail buck in New York or a bull elk in Colorado. The ability to beat dismal odds of 20 percent or less to fill your tag instills a heady pride, one where you can pat yourself on the back and wear a big smile all the way home.

Connecting with People

Those of us who love to shoot find hunting the perfect way to fulfill that desire while enjoying the bounty and traditions of hunting. I’ve hunted doves most of my life, but last year I experienced my first-ever classic Southern dove shoot. There were about a hundred of us. We started with a group prayer, then tore into barbecued pig, potato salad and sweet tea before heading to the fields. It was fun, not only the shooting but the camaraderie as well.

I’m fortunate to have spent most of my life in the woods—5 years earning degrees in forestry and wildlife, 15 years as a forester and wildlife biologist and 24 years as a full-time hunting writer. Yet despite a lifetime in the outdoors, I still yearn to hunt, more than ever, whether it’s new country or old country, where every ridge and valley holds a memory. As someone who hunts more than 160 days a year, I’m often asked if it ever grows old. My answer is, “Absolutely not!” I still thrill at the prospect of annual trips with old pals, like the Iowa deer hunt where I can’t wait to climb into the familiar tree stand each December; or the South Dakota pheasant hunt where I love to walk the cattails along my farmer buddy’s lake; or the Colorado elk hunt where I climb a damnable mountain, hoping to spot an elk in a meadow below; or the Wyoming turkey hunt where I can almost always count on roosting a bird on my favorite ridge every afternoon. These are rituals, traditions that excite me to the point that I don’t sleep well the night before each hunt.

A Taste of Freedom

Another major reason I love to hunt is that hunting offers me total freedom to do exactly what I want to do and make my own decisions in a world untrammeled by the chaos of society. Think about that. Other than wildlife laws and regulations, there are no governing “rules” when we hunt, aside from the ethical ones we impose on ourselves. In golf you must follow a set course; in bowling, tennis or any other sport, you must adhere to strict criteria. When you drive you must follow a road. In society you are expected to follow certain rules of behavior. But in the woods, you’re out there by yourself, making your own decisions, perhaps contending with severe weather, insects, snakes, perilous obstacles, rugged and treacherous terrain, avoiding becoming lost and essentially taking care to keep yourself safe and comfortable. You carry a firearm or razor-sharp arrows, and a careless move can change your life in a heartbeat. You answer to no one—no bosses, spouses, parents or siblings. You are free, finally! The rest of the world be damned for that precious window of time when you can enjoy the wildness, the sounds, the smells and the sights of a world so far removed from our everyday lives.

Who among us doesn’t thrill to the birth of a new morning, as the dark of night turns to murky gray and finally, very slowly, to a glorious sunrise as the sun peeks over the eastern horizon? As we sit there witnessing that magical transformation, we hear the first bird chirp, and perhaps the crowing of a distant barnyard rooster or the barking of a farmer’s dog. There is a special satisfaction in knowing that most of the rest of the world around us isn’t hearing those sounds. It’s all good, whether we squeeze the trigger, release the arrow or go home with just a memory.

Cameras Don’t Cut It

Some people have asked why I must hunt with the objective of killing the quarry. Why, they wonder, can’t I simply walk the woods with a camera and record my encounters with wildlife on film? The answer is simple: to do so is not hunting. A photographer is an observer; a hunter is a participant in the outdoor drama. I firmly believe that those of us who choose to hunt are predators. Let us make no excuses for that definition. Our prehistoric ancestors hunted, and so we follow those traditions. In my view, “the chase” is an essential part of my very being, whether it’s tracking a bull elk in powder snow, or shivering in a blind waiting for a flock of geese to commit and drop into my decoys. Nothing dies easily in the woods. Animals perish, with or without our help. Most of them die violently and painfully, perhaps in the talons of a hawk, in the jaws of a coyote or as a victim of starvation or disease. My kill is quick and humane. And make no mistake, hunting by humans is natural. Man has always hunted. Don’t let anyone convince you otherwise.

I don’t rationalize my love of hunting by saying that I’m a “wildlife-management tool” essential to keep some animal population trimmed, nor do I hunt because my money funds wildlife agencies that ensure the propagation of all creatures, be they endangered or legal game. Yes, hunting and the dollars generated by license fees are tremendously helpful to wildlife, but first and foremost I love every aspect of hunting with every cell of my body for all the reasons I have just tried to explain. My attempts at explaining it are merely words that mean nothing to those who have never hunted.

If you are a hunter, however, you know. We’re a fraternity, very definitely in the minority, a collection of people with a never-ending love of everything the outdoors offers. We are maligned, cursed at and spat upon. Every day people try to outlaw our sport. Those souls have no clue what we feel.

I hunt because I exist. And I am, above all, proud to be a hunter.

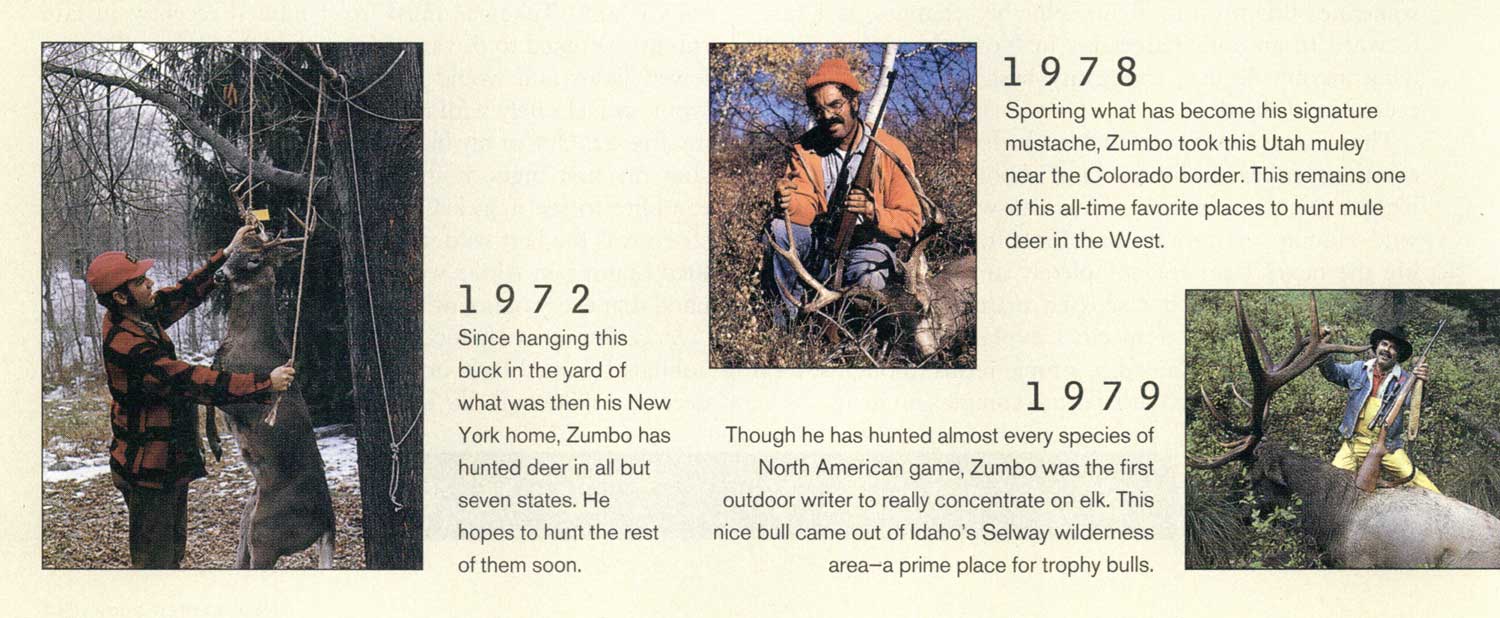

A Career in Hunting

1972: Since hanging this buck in the yard of what was then his New York home, Zumbo has hunted deer in all but seven states. He hopes to hunt the rest of them soon.

1978: Sporting what has become his signature mustache, Zumbo took this Utah muley near the Colorado border. This remains one of his all-time favorite places to hunt mule deer in the West.

1979: Though he has hunted almost every species of North American game, Zumbo was the first outdoor writer to really concentrate on elk. This nice bull came out of Idaho’s Selway wilderness area—a prime place for trophy bulls.

1987: Zumbo and guide Debbie Overly teamed up to take this full-curl Dall sheep in Alaska. This hunt was extremely rugged and required horses and plenty of climbing.

1991: Zumbo’s favorite time to hunt elk is in the late season, when heavy snows drive big bulls down out of the high country. The tradeoff is bitter cold conditions that tax hunters to the max.

1995: Like most hunters, Zumbo always dreamed of going to Africa. His dream came true in 1995 when he went on his first safari.

2001: This woodland caribou from Newfoundland was the last of five species Zumbo needed to complete his grand slam.

From the Field

Todd Smith, Editor-in-Chief: “I hunt because my father hunted, just as his father hunted before him and his grandfather before that. Hunting is a part of who I am, a part of how I define myself: I am ‘a hunter.’ I hunt because it is one of the last great challenges left on earth. I hunt because I love hunting. Not to hunt would require me to give up something that’s truly important. I’m simply not willing to do that.”

Jim Carmichel, Shooting Editor: “I’ve always hunted, and every worthwhile person I know hunts. Hunting is as American as Independence Day and Mom’s apple pie. No reasons or explanations for hunting are necessary. Anyone who feels compelled to explain why he hunts should probably take up some other sport.”

John Wootters, Writer and Whitetail Expert: “First, I hunt for food, of a variety and quality that I cannot legally purchase at any price, a grade of meat of which the only source is the living wild animal. Second, I fulfill my urge to have direct personal involvement with the dramas of real life in the real world, where hunters are actors, not merely watchers. Third, and most profound: Hunting is a human genetic imperative. Not to hunt, therefore, is simply unthinkable.”

Michael Hanback, Contributing Writer: “My dad always made the time to take me with him. I remember the the first squirrel I killed, the first turkey I missed, my first buck and how incredibly hot its blood was on my hands. Will Hanback was at my side for it all, teaching, laughing, consoling, stern when he had to be. That kind of parenting molds you. For forty years it has kept me going back to the woods for more.”

Jack O’Connor, Former OL Shooting Editor: “I wish Grancel Fitz hadn’t started it all [the grand slam]. The old-timers hunted sheep because they loved sheep, because they loved to be up on those high, windswept ridges where they shared the sheep pastures with the sheep, the grizzly, the hoary marmot, the soaring eagle. When they brought back a ram trophy, they were not seeking honor and prestige—they were bringing back memories of icy winds fragrant with fir and balsam, of the smell of sheep beds and arctic willow, of tiny, perfect alpine flowers, gray slide rock, velvet sheep pastures.”

Brenda Valentine, Bass Pro Team Member: “I hunt because of a need that comes from deep within, which is not so very different from hunger or thirst, a need that I feel was imprinted into the genes of early man for survival of the species. Along with this urge to hunt is a desire to wake up and hone my natural senses, and to pit these senses against the superior ones of the animals I pursue. Hunting and the entire outdoor experience give me an emotional cleansing, a spiritual connection and a physical rejuvenation.”

Chuck Yeager, Test Pilot: “Quail hunting is probably the outdoor activity I enjoy most. It satisfies my constant longing to be in natural, unspoiled places; it provides a physical and mental challenge. And because it’s best when approached as a kind of team sport, it allows me to spend time with Bud Anderson, my comrade when we were in dogfights in World War II. Oh, and one more thing: It puts some darn good food on the table.”

Jack Atcheson Sr., Booking Agent: “I hunt because I simply love being in the outdoors. I especially love chasing elk in the rugged, scenic mountains but I’m also happy hunting sage grouse and antelope on the prairie. My ancestors hunted for meat, and so do I, but it’s not necessary to pull the trigger to have a great hunt. In fact, I may let a dozen or more bull elk walk by during a season, and if I take one, I know he’ll be replaced by a calf that will be born the following spring. I feel I am as much a part of nature as the wolf, mountain lion and grizzly bear.”

Dan Zumbo, Jim’s Son: “Hunting is an art form that provides an experience like nothing else. Hunting means beautiful mornings, cold, wet days, the blast of a shotgun, the sound of a dove’s wing beat, the sight of a hardworking dog, the toil of dragging a deer up an infernal slope, the camaraderie of family and friends, the BB gun in the backyard, the taste of venison stew, those endless ‘be careful’ comments, daydreaming in the stand and the eternal hope for another day in the field. Nowhere will you find as much enjoyment as in this opportunity that we all have.”

Read more OL+ stories.